Muslims have the same human needs, desires, struggles, and spiritual questions as Christians do.

Larry Lichtenwalter

There is no question that a knowledge and understanding of the Qur’an is an indispensable condition in relating meaningfully to Muslims, whose worldviews, customs, daily rituals, speech, and thought patterns have been indelibly shaped by the Qur’an and its ethos. Knowing Muslim scriptures and their culture holds out the prospect of better communicating the gospel. But how so?

Does the Qur’an contain redemptive analogies that can be used as bridges to present biblical faith? Or would its direct and tacit subversion of the essential elements of the gospel deny such and press one to find ways to better present biblical faith? Lively conversation continues regarding the legitimacy of using the Qur’an as a bridge to the Bible or not at all.

When I propose thinking biblically about the Qur’an, I do not have in mind the reading of the Qur’an through biblical eyes (the Bible as an under-text) in order to unfold biblical gospel themes from the Qur’an for Muslims. Rather, I intend critical, biblical engagement of the Qur’an’s “inner logic” system on the macro- hermeneutical level in order to better use the Bible in gospel work among Muslims. It assumes that the Qur’an exhibits a core logic. If so, then that inner system inevitably affects the interpretation of its parts. If the Qur’an has no core logic, then its text is open to the confusion of multiple interpretations, including Christian eisegesis.

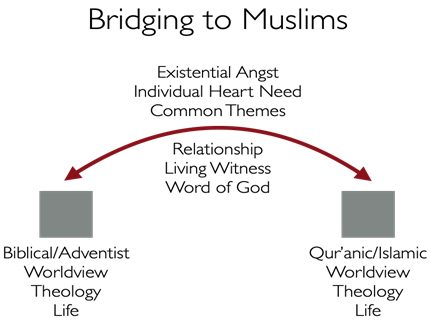

The gospel worker’s goal is unfolding gospel themes from the Bible in relevant ways for his or her listeners. In Muslim contexts, that is best accomplished when the worker understands the Qur’an’s core logic. In doing so, he or she can better imagine the existential impact that the Qur’an’s worldview has on the Muslim soul. We will not know how to use the Bible most effectively in Muslim contexts until we understand the real soul need of Muslims as nuanced by their exposure to the Qur’an—its worldview and ethos. This is a fundamental starting point for mission.

Thus, the question of bridging to Muslims should be reversed: Rather than “How do we better use the Qur’an as a bridge to lead Muslims to the Bible?” we should ask, “How can we better use the Bible as a bridge to lead a Muslim to the Bible?” This requires a deeper understanding of the Qur’an than what biased eisegetical and proof-text approaches—which manipulate the text for missional purpose—can enable. It requires also a deeper understanding of the Bible on its own macro-hermeneutical worldview level.

Our question here is not whether one uses the Qur’an in gospel work among Muslims. That is a given. Rather, we ask: Why do we use the Qur’an? When do we use it? How do we use it? Do we allow the Qur’an to speak for itself, or are we manipulating the text via Christian qur’anic eisegesis? In what way is the Qur’an advanced as an authority? Is it ethical to create redemptive analogies/bridges from qur’anic phrases and texts that were never intended for use in that way in either their immediate context or in the Qur’an’s core metanarrative? Most of all, how can we nuance biblically relevant theological or soteriological themes from the Qur’an without implying that the Qur’an authoritatively teaches such? At bottom is the question: To what hermeneutical and ethical guidelines are we bound when handling Islam’s holy text?

We ask these questions knowing that the Qur’an is positive toward both Jesus and what we today call the Bible. But how so? And can the missional bridge between what the Qur’an means and the truths of the Bible be unwittingly dulled or short-circuited by Christian eisegesis of the qur’anic text?

This study asserts that the Qur’an has its own hermeneutic, together with a complex labyrinth of interpretive prism and historic precedent. If so, one must first analyze qur’anic concepts within their own historic and literary contexts as well as within the Qur’an’s own worldview and interpretative framework (core logic). Only then can qur’anic concepts and their equivalents in both the Old and the New Testaments be analyzed with integrity—and in a way that (1) allows the Qur’an to speak for itself and does not impose on it a contrived Christian reading or meaning, i.e., eisegesis; and (2) enables the gospel worker to use God’s Word wisely and effectively in response.

Accordingly, we explore four aspects of the Qur’an in relation to the Bible: its self-image, worldview, hermeneutic, and Christology. This informs two critical concerns of gospel work among Muslims: the position and status of the Bible in relation to the Qur’an on the one hand, and the person and work of Jesus on the other. Clarity of what the Qur’an does or does not say on these two issues inevitably determines the kind of bridge one can and/or needs to create.

Some orienting principles are helpful if we would think biblically about the Qur’an: (1) the difference between a Muslim and Islam; (2) the hermeneutical priority of biblically informed worldview and cosmic conflict narrative; (3) the revelation of God’s character of love; and (4) the finality of God’s revelation in Jesus Christ. Additionally, there are two assumptions: (1) that the Qur’an is not an inspired document in the biblical sense or in keeping with the Bible’s core logic, worldview, values, redemptive trajectory, view of God and finality of God’s revelation in Jesus Christ; and (2) that Muhammad is not a prophet of God in the biblical sense. If these assumptions are valid, how then do we relate to apparent biblical truths or values that may be found at least on the surface level in the Qur’an?

Qur’anic Self-Image

The apparent “self-referential” nature of the Qur’an nuances our understanding on a macro-hermeneutical level. The Qur’an is highly self-aware. It observes and discusses the process of its own revelation and reception. First, as a vertical “sending down,” tanzil, which simultaneously connotes two things: (1), a descent of something exalted; and (2), a gradual dispensation. That is to say, the Qur’an is exalted “Divine speech that was dispensed in portions over many years, such that it may be easy for people to understand, digest, and put it into practice.”1

Second, as “inspiration” (waḥy) in which there are three kinds of revelations. There is waḥy Khāfī, the “inspiration of ideas into the heart,” which is called “inner revelation,” that is to say, God speaking to human beings that is common to prophet and non-prophets alike. Second, there is min warāi' hijab, “from behind a veil.” In this type of waḥy, God speaks to people in dreams, visions, or in certain meditative states and trances. The third type of waḥy is the highest form of revelation, meaning waḥy matluww, “revelation that is recited in words.” This kind of waḥy is best illustrated in Gabriel’s giving of the divine message of the Qur’an to the prophet Muhammad.

The third waḥy asserts its own authority and claims its place within the history of revelation. It maintains kinship with revelations to Christians and Jews, mostly in terms of bringing the same message of the need to repent and to turn to the one God. In doing so, the Qur’an assumes that the God it speaks of/for is the God of the Bible. It does not, however, claim to be textually dependent on earlier scriptures.

While the Qur’an assumes that it contains the same message that was given to previous prophets and messengers, its concerns are not the same as the earlier revelations that it references. It sees itself not so much as a completed book but as an ongoing process of divine “writing” and “rewriting.”2 This includes confirming and completing earlier monotheistic revelations as THE final revelation, which both subsumes and supersedes them. Orality is central. So also is communal formation through proclamation and liturgy. Yet the Qur’an does see itself as comprising the last of a series of books that communicate God’s will for humanity. It asserts and reflects the heavenly prototype—“Mother of Book” (Umm al-Kitâb), i.e., the source of all revealed scriptures among Abrahamic monotheistic religions. Ultimately, the Qur’an lives not on paper, but in the hearts of the “unlettered” to whom Muhammad was sent.

The Qur’an reflects familiarity with many biblical characters, though with only a sketchy core of their stories and with a different perspective. Most if not all the prominent biblical stories and characters found therein have been significantly edited or altered. Major defining portions of some biblical narratives have been deleted. New material has been added to the text/story line of others. Narrative details are systematically changed and/or “corrected” by the qur’anic version. A given biblical narrative or Bible character’s focus and meaning have been altogether eclipsed or changed with a new application or meaning in relation to Muhammad as a spokesman for God or Islam as a whole. Bible characters and references to the coming Messiah are applied to the person, work, and existential struggles of Mohammad’s prophetic journey.

The Qur’an addresses multiple themes that are significantly expanded in the Bible. On four occasions it invites readers to go to these expanded, earlier revelations for confirmation of its own message. These referrals to earlier revelations, however, do not imply any independent authority status on their part as much as they allow Muhammad to posit his message as consistent with what has been revealed before. Intentionally however, “The Qur’an often plugs biblical words, concepts and narratives into its own very different theological grid, giving them very different meanings,”3 something only alert and biblically informed readers detect. It appears that Muhammad drew largely from Jewish and Christian non-biblical oral tradition, rabbinic lore, and literature with very little accurate biblical text or biblical language.

Nowhere, however, does the Qur’an itself (or even Muhammad for that matter) overtly criticize earlier revelations. The Qur’an is always positive toward such. So also, Muhammad. However, the Qur’an is otherwise ambiguous on its relationship to them. Understanding this nuance is important in utilizing the Qur’an accurately when bridging Muslims toward the Bible.

Our concern, though, is not that the Qur’an consistently looks favorably on earlier revelations, which we call the Bible, but rather:

1. What the Qur’an really has in view when it refers to these earlier revelations. Is it the Hebrew Scriptures in their textual entirety? Or is it non-scriptural Rabbinic literature, oral tradition, and legends? Is it the New Testament Scriptures in their textual entirety? Or is it apocryphal Christian literature and/or their perceived errancies?

2. How the Qur’an actually handles and utilizes these earlier revelations. Does it do so in a way that is consistent with the Bible’s own context, meaning, and purpose? How does it position these earlier revelations in relation to itself—the Qur’an—and to Muhammad?

3. What the Qur’an confirms, clarifies, protects. Is it the biblical text in terms of its content and intended meaning, or is it Muhammad’s (and the Qur’an’s) “corrective” interpretation of these earlier revelations?

These are important questions. Ultimately, what the Qur’an actually does with these earlier revelations—the Bible—is quite revealing.

First, the Qur’an appears to assume that the earlier revelations are part of an eternal heavenly prototype, i.e., the “Mother of Book” (Umm al-Kitâb), which is the source of all scriptural revelations, and which now through the Qur’an, provides corrective completion. This heavenly archetype is the perfect original Qur’an, an otherworldly copy of the text. As such it exists in eternity with God, or in God’s mind, as a whole and complete book; the Qur’an states, “With Him [God] is the original of the book” (Sūrah 13:39).4

This heavenly book is seen as the “Mother” or origin of any and all revelations that God communicates to human beings—reflecting a Heavenly Recitation (Qur’an) that is the eternal archetypal source of all divine revelation. The implication is that all of God’s revelation throughout all of history and through all the prophets has been essentially the same message and within the umbrella of the Mother Book. This is flawless communication from God. It simply means that earlier revelations—Torah of Moses, book of David, gospel given to Jesus, respectively—are part of the Umm al-Kitâb (Mother of Book) and that the ‘Ahl al-Kitāb (the People of the Book, i.e., Jews, Christians, and Sabeans) are essentially viewed in relation to the Qur’an as an overarching paradigm and not respective texts per se. In effect, one is only truly part of the “People of the Book” when he or she accepts the Qur’an and believes in Muhammad.

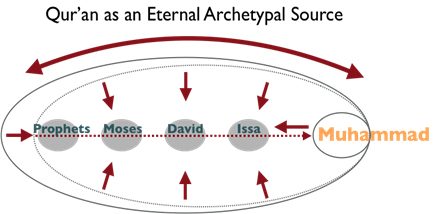

The implications for earlier revelations—the Bible—in relation to the Qur’an can be visualized in the following figure:

Figure 1: The solid elliptic represents the encapsulating revelation of the Qur’an, of which earlier revelational periods enumerated in the dotted elliptic are envisioned. The final smaller solid elliptic reflects the emergence of the Qur’an as a recited and completed whole of the “Mother Book” in the life of Muhammad.

Second, the Qur’an appears to assume that Muhammad (and Islam) are the intended focus of previous revelatory segments: “Those who follow the Messenger [Muhammad], the unlettered prophet, whom they find inscribed in the Torah and the Gospel that is with them, who enjoins them what is right, and forbids them bad things . . . those who believe in him, honor him, help him, and follow the light that has been sent down with him; it is they who shall prosper.”5 It is in this sense—i.e., the former revelations point to Muhammad and Islam—that the Qur’an is the “confirmer” and “protector” of the earlier revelations:

“He sent down the Book [Qur’an] upon thee in truth, confirming what was before it, and He sent down the Torah and the Gospel aforetime, as a guidance to mankind. And He sent down the Criterion” (3:3);

“He it is Who has sent down the Book [Qur’an] upon thee; therein are signs determined: they are the Mother of the Book” [Qur’an] (3:7);

“And we have sent down unto thee the Book [Qur’an] in truth, confirming the Book [Torah, Gospel as part of the Qur’an] that came before it, and as a protector over it. So judge between them in accordance with what God has sent down” (5:48).6

Thus, the Qur’an presents itself as confirming the validity of previous scriptures and its unchanged message in keeping with the ethos of the “Mother of the Book.” In doing so, it guards the true meaning and interpretation of earlier revelations. In effect, it provides the true meaning and an additional interpretation of the Bible. It is for this reason that Muhammad would rail against Jews who allegedly were misinterpreting or hiding passages about him from the earlier revelations.

However, the Bible and the Qur’an reflect different revelatory origins, historical contexts, and narratives. While the Qur’an came into being within the historic and cultural context of one supposed prophet and within a single generation, some 40 different divinely inspired prophets/authors spanning more than 15 centuries and multiple cultural contexts penned the Bible. This is a significant differential with reference to the question of progressive revelation and foundational truth.

The Bible testifies to a progression of God’s revelation of Himself to humanity (Heb. 1:1, 2). Divine revelation was given in stages (Rom. 16:24, 25; Heb. 1:1, 2). God did not reveal the fullness of His truth in the beginning—yet what He revealed was always true. The progressive character of divine revelation is recognized in relation to all the great doctrines and themes of the Bible. What at first is only obscurely intimated is gradually unfolded in subsequent parts of the sacred volume, until the truth is revealed in its fullness. Each portion of the Bible builds on the previous one(s). Earlier revelations, while accurate, are incomplete. Later revelations, while providing further and fuller information, in no way contradict or abrogate what came before. Nor do they stand alone, independent of what has been revealed by God before. Rather, later revelations clarify and amplify the things previously revealed. In this context, from a biblical perspective, the ultimate revelation of God is understood to be found in Jesus Christ as revealed in the Gospels (Heb. 1:1–4; Jude 3; John 1:1–14, 18; Col. 2:2, 3, 8–10; 1 Cor. 1:30).

Progressive revelation assumes a God who does not change (1 Sam. 15:29; Ps. 110:4; Mal. 3:6; Heb. 1:12; 7:21). It assumes, too, theological/moral correspondence and coherence, foundational truth and enlargement, and prophetic anticipation and fulfillment (Isa. 8:20; Luke 24:27, 44, 45; Acts 18:28; Rom. 1:2; 16:26; 1 Cor. 15:3, 4; Heb. 1:1–4; 8:1–10:23).

Furthermore, within the biblical context, it is the earlier, fragmentary and incomplete revelation—what comes before—that is foundational and which confirms and checks the validity of later revelation (Isa. 8:10; Luke 24:27, 44, 45). In keeping with God’s progressive revelation, the centuries unfolded an expanding, coherent resource of inspired light, thought, and guidance, which became the theological foundation for critique and/or confirmation of subsequent revelation—especially so with the close of the biblical canon (Isa. 8:20; 2 Tim. 3:16, 17).

How the Qur’an and Islam testify to this biblical phenomenon of progressive revelation with the Bible’s “fullness” in Jesus Christ determines their ultimate credibility. The Qur’an asserts its own message as the final confirming, protecting, and corrective revelatory criterion of God (Sūras 5:48; 3:3). But it seems to do so at the expense of earlier revelations that appear in the biblical canon. The Qur’an essentially marginalizes the fullness of the New Testament gospel witness in general and the finality of God’s revelation in Jesus Christ in particular. Rather than being confirmed by earlier revelations as per the Bible’s ethos, the Qur’an positions itself as confirming the integrity and content of all earlier biblical revelations. It should be noted that from an Islamic perspective, a “revealed book alone does not make a perfect guide and that a teacher is needed who, by his superior spiritual knowledge and practical example, should lay bare its hidden beauties and excellences.”7

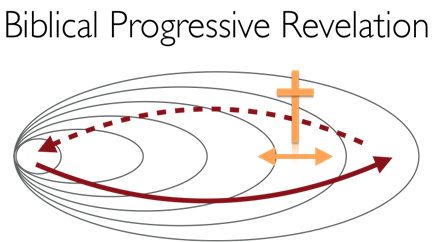

In keeping with its Umm al-Kitâbi (“Mother Book”) perspective as noted above, the implications for earlier revelations in relation to the Qur’an can be illustrated using Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2: Each expanding elliptic includes the core of the earlier, both expanding earlier meaning and looking back to its truths for confirmation. The person and work of Jesus Christ assumes the past and unfolds the meaning of the future.

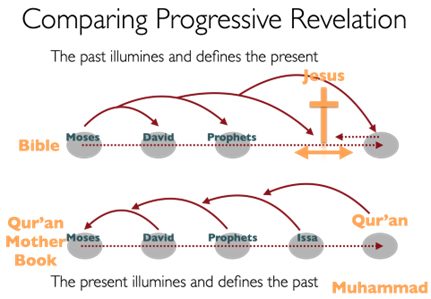

A comparison of the implications for biblical and qur’anic revelatory foundations and authority are revealing. For biblical revelation, the past illumines and defines the meaning of the present, while for qur’anic revelation, the present illumines and defines the meaning of the past.

Figure 3: For progressive revelation in the biblical perspective, the past illumines and defines the present, while in the qur’anic perspective, the present illumines and defines the past.

Qur’anic Worldview

The Bible and the Qur’an generate unique worldviews. Sacred writings generate worldviews in keeping with their respective meta-narrative, reasoning, and symbolism. The assertions that each worldview both presupposes and projects about God, reality, the world, and human beings profoundly affect one’s identity, spiritual experience, and ethics. Because the biblical and qur’anic worldviews are largely defined by a vision of God, there is a need to explore the qur’anic witness of Allah in relation to the biblical witness of the being and character of God. Their different historical contexts, revelatory content, moral themes and ethics, views of human nature, soteriology, and spiritual life—which these two books narrate differently—likewise need consideration from the macro-hermeneutical perspective.

This study does not propose to compare the biblical and qur’anic worldviews in detail, but will simply note that despite numerous surface similarities and themes, “the two worldviews are profoundly different.”8 This profound difference inevitably nuances hermeneutics and the interpretation of their respective texts. Their specific content and context become key factors in determining meaning. With reference to the Qur’an, no matter what individual qur’anic texts may seem to say or affirm on a phenomenological level with reference to analogous concepts with the Bible, it is necessary to allow their respective worldview and theology to guide our understanding of what they really mean.

While much can be said about the qur’anic worldview, three defining themes permeate and dominate: (1) the oneness and transcendence of Allah; (2) the nature and purpose of the Qur’an; and (3) the person and work of Muhammad in relation to both Allah and the Qur’an.

Muslim devotion begins with the Shahada: “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the messenger of God.” One does not find this precise formula anywhere in the Qur’an (the concept however, is enforced in Sūrah 112). Nevertheless, “the Qur’an clearly attests that there is no God but God, even as it witnesses to his having sent down his revelation to his prophet or messenger, Muhammad.”9 Allah, the true Reality, “is historically revealed through the mission and prophethood of Muhammad. The Prophet Muhammad is the embodiment of the divine message and not a reflection of the divine Person.”10 Furthermore, the Qur’an “unequivocally urges obedience to both God and Muhammad, which is the creed’s practical import.”11 Obeying God and the prophet Muhammad is one of the Qur’an’s top ethical priorities. At times, the distinction between God and the prophet Muhammad blur. Additionally, the prophet Muhammad’s “night journey” to Jerusalem and then on to heaven (17:1) positions him in a cosmic dimension unifying the horizontal and vertical spheres of heaven and earth. Thus, the Qur’an “centers Muslim life in obedience to both God and Muhammad.”12 To obey the Qur’an is to obey both God and the prophet Muhammad. The Qur’an provides the ideal, a constant in terms of eternal values, i.e., moral/spiritual guidance and light, while the prophet Muhammad provides the example of the real, the praxis of what it means to be Muslim.13 This places the prophet Muhammad in a unique relation to both God and the Qur’an. Muslim reactions to criticism of Muhammad are very strong and passionate.

Within this worldview, reality is divided into two generic realms: God and non-God, in which God “remains forever transcendental Other devoid of any resemblance, similarity, partnership and association.”14 He is true Reality, true Being. He stands alone: absolutely transcendent. This view of reality concerning the belief in one God nurtures “a commitment to radical transcendental monotheism.”15 To embrace this truth is to enter into the life of a community of faith, namely, Islam. It “occupies Muslim thought and action and polarizes the thought of Islam into real and non-real.”16

Theologically, writes Shah, “that God posits a strict uncompromising ethical monotheism, signifying the absolute Oneness, Unity, Uniqueness and Transcendence of God, in its highest and purest sense, and which formally and unequivocally eliminates all notions of polytheism, pantheism, dualism, monolatry, henotheism, tritheism, trinitarianism, and indeed any postulation or conception of the participation of persons in the divinity of God.”17

Corporeal notions and anthropomorphic images of God’s being are avoided. For that reason, Ahmad Gunny states that “Muslim theologians insist that anthropomorphic terms applied to God were to be taken vaguely, without specifying literally or metaphorically.”18 God is nowhere comparable to anthropomorphic images, for such may lead the believer to natural theology. God is not in things, and creation is other than God. For Sūrah 22:18a says, “Do you not see that to Allah bow down in submission [i.e., prostrate, all beings submit to His Will].”

Metaphysically, the Qur’an’s radical monotheism implies correlation between the Oneness of God and the oneness of existence—Tawḥīd. It rejects dualistic dichotomy and allows “the sacred to dissolve and overcome the profane, merging life into a God-centered whole, suffusing every aspect with a consciousness of the divine.”19 “It unifies material life with the spiritual realm and gives conceptual framework and meanings to this worldly life so much so that the transformation of time and space become an urgent matter, of great concern to man here and now.”20 This oneness of God and the oneness of existence effectively eliminate boundaries between religion and politics.21 It was Ibn ‘Arabi (1165–1240), who expounded on the doctrine of Being and who first formulated the belief that the oneness, unity, and unicity of God forms the essence of the Islamic vision of reality.22

While merging all of life into a God-centered whole, the ontological hierarchy of being implied in Islam’s divide between God and non-God asserts, however, that the order of time-space, creation, and of experience remain in a realm in which God is both distinct and distant from His creation. True Reality (Allah) is historically revealed through the mission and prophethood of Muhammad, not through anything God Himself might do. God is essentially unknowable in His self-sufficiency and unicity. His existence, for the Qur’an, is strictly functional. While intensely theocentric to the core, the Qur’an is not about God per se, but on revealing the commands of God.

In the words of Kenneth Cragg, “The revelation communicated God’s Law. It does not reveal God Himself. . . the genius of Islam is finally law and not theology. In the last analysis the sense of God is a sense of Divine command. In the will of God there is one of the mystery that surrounds His being. His demands are known and the believer’s task is not so much exploratory, still less fellowship, but rather obedience and allegiance.”23

Within this paradigm, God is essentially timeless. Respectively, the insistence upon God’s absolute transcendence and perfect unity has unique implications for questions about the nature of God, free will and predestination, the relationship of good and evil, and of reason to revelation.

The foregoing vision of Tawḥīd—including visible/invisible spheres where the transcendent invisible bestows meaning to the visible and where Allah is the singular, ultimate, invisible, unseen, and unknowable divinity—implies a tacit Middle Platonism. Greek philosophical presuppositions—both Platonic and Aristotelian—have had a significant influence (directly and indirectly) on Islamic thought.24 In a milieu already saturated with Plotinus and Aristotelian thought, it occurred unintentionally at least during Islam’s formative years as Muhammad both engaged and absorbed Christian, Jewish, and Zoroastrian religious thought. The metaphysical beliefs of the pagan environment and Bedouin culture of Muhammad’s day likewise shaped philosophical and epistemological understandings in keeping with Platonic perspectives. Ultimately, Platonic influence would become more nuanced as Islam conquered Alexandria a century later, becoming overt and systematic during the Abbasid Caliphate in ninth to 10th-century Muslim scholarly projects.

Surprisingly, and almost contradictorily, an underlying animistic belief system (worldview) replete with tacit spiritual power-related implications exists in the Qur’an. This underlying animistic worldview system includes fear, power, and magic. There are evil powers: ghosts, jinn (literally “hidden” or “concealed”), demons, evil eyes, curses and sorcery. Two Sūrahs (113, 114) are “used by Muslims to this day for protection from many evils, including the evil eye and the casting of spells.”25 This qur’anic spiritual cosmology is further nuanced by numerous references to Jinn (Sūrah 7:38, 179). Muhammad’s recitation of the Qur’an is associated with the presence of jinn. While the Sūrat Al-Jinn asserts the submission of all spiritual entities, including the jinn, to God, they nevertheless exist as intermediate beings with good or bad powers. One’s only protection is to seek the aid of Allah, charms, good magic, and other powers. Undoubtedly, this is inconsistent with orthodox Islam’s radical monotheistic stance, which eschews any such notion. Yet beneath this theological veneer is a world of power(s): power people, power objects, power places, and power times, i.e., folk Islam. Animism believes in innumerable spiritual beings concerned with human affairs and capable of helping or harming human interests.

Ritual similarities between the pre-Islamic pagan (Jahiliyyah)—“Time of Ignorance”—the Kaaba and the Muslim Hajj regimen at the Kaaba suggest the resilience and adaptation of Bedouin animistic customs that were heathen in nature, some which Muhammad modified or repurposed when he cleansed the Kaaba of its many idols and categorically rejected polytheism. While Muhammad may have cleansed the Kaaba of its idols, the fundamental philosophical and cultural core of Kaaba power-related worldview and ritual remain. Despite Islamic orthodoxy, this animistic heritage underlies much of what Muslims actually believe and do. This can be said of Christians as well. However, unlike the biblical worldview, Islam’s sacred sources (the Qur’an and Hadith) together with the prophet Muhammad’s own practice unwittingly foster belief in spiritual beings, practices, or sacred objects capable of helping or harming human interests.

Suffice to say, the Bible presents an altogether contrasting worldview. A cosmic conflict metanarrative (warfare worldview) provides the conceptual backdrop for understanding God, evil, the human predicament, freedom, judgment, redemption, and destiny (Genesis 1–3; Job 1:6–2:7; Isa. 14:3–21; Eze. 28:1–19; Dan. 2, 4, 7, 10, 11; Rev. 12:1-17). Its monotheism asserts the relational triunity of God. Its anthropocentric analogies unabashedly reveal God as personal in relation to human beings and all His creation. The person and work of Jesus Christ display God’s character of love. In His person and work, Jesus brings the fullness and finality of God’s redemptive revelation in human history as well as the centrality of Jesus over all. God is eternal rather than timeless. History is the arena of God’s activity in human affairs. He is not only transcendent Creator, but immanent Father, Redeemer, Sustainer. Jesus’ incarnation reveals God’s action in both human time and space.

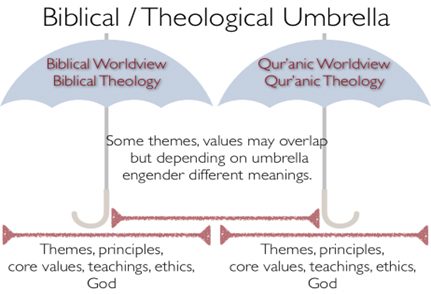

Figure, 4’s Worldview Umbrellas describes the implications of overlapping worldview themes and how real meaning is determined by the Worldview Umbrella under whose influence a person resides.

Figure 4: Like an umbrella, a worldview engenders meaning, which includes defining themes, principles, core values and logic, teachings, ethics, and a view of God. A given worldview may intersect with another worldview in which some themes or values overlap phenomenologically; nevertheless, each respective worldview may engender different meanings on the deeper macro-hermeneutical level.

Qur’anic Hermeneutics

We have asserted above that the Qur’an has its own hermeneutic together with a complex labyrinth of interpretive prism and historic precedent. It is a given that “many passages are obscure, and cannot be understood without reference to the substantial body of exegetical literature, derived from the oral Hadith-traditions which came to be selected and written down around the third century of Islam.”26 We have also asserted that one must first analyze qur’anic concepts within their own historic and literary contexts as well as within the Qur’an's own worldview and interpretative framework in relation to that of Islamic thought and life. Only then can one critically analyze qur’anic concepts and their equivalents in both the Old and the New Testaments with integrity. “Biblical studies is often invoked as a methodological parallel in discussing the Qur’an.”27

While the Qur’an is increasingly being subjected to analysis by the instruments and techniques of biblical criticism, “the parallel is dismissed and an appeal is made to the singularity of the Quran as a piece of Arabic literature and therefore a need for a distinct methodology.”28 Three approaches have emerged as dominant in contemporary qur’anic studies: semantic studies, literary structural studies, and historical-contextual studies.

The historical-contextual studies approach includes reading the Qur’an chronologically. It assumes that a chronological reading of the Sūras (chapters) of the Qur’an, supplemented with Muslim commentary literature and biographical materials of the life of Muhammad, provides the clearest context for understanding the Qur’an—although not every Sūrah fits nicely into this rubric. This approach places the Qur’an in a broad historical/cultural context and milieu. It allows the reader to trace Muhammad’s evolving religious viewpoint based on his trajectory of conflicts with pagan, Jewish, and Christian audiences. The reader can observe, too, how much Muhammad borrowed Jewish lore and Christian mystic oral traditional/apocryphal materials as evidenced in the qur’anic text and explanatory Hadith. A chronological read allows macro-hermeneutical reflection as worldview, philosophical, and theological assumptions/assertions surface across the developing historical spectrum.

While the purpose of the above qur’anic study approaches is for the Qur’an to speak for itself, a further systematic critical engagement of the Qur’an on the macro-hermeneutical level is essential. This qur’anic macro-hermeneutical perspective is an essential first step when relating to the book’s worldview and the intended meaning of its words, patterns of thought, and existential import. No matter how individual qur’anic passages, words, phrases, referents or rhetoric may seem parallel with biblical concepts, the Qur’an’s own overarching worldview and theology must first be allowed to surface as a guide toward understanding of their intended meaning. Exegetes and interpreters know that words find and/or are given meaning within specific literary contexts. Worldview reflection as expressed in literary contexts nuances the meaning of words, turn of phrases, figures of speech, and rhetoric. Once such has been observed with the Qur’an, critical biblical theological engagement on this macro-hermeneutical level becomes appropriate.

This biblical macro-hermeneutical assessment best begins with the Qur’an’s early Sūrahs, which are brief, pithy, poetic, and engaging, and foundational to qur’anic thought. These early revelations open up rich worldview perspectives. Foundational themes relating to the nature of reality, God, ontology, epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and the human being emerge. Many read like the biblical psalms with themes and rhetoric and turns of phrases that engage the reader. These early Sūrahs are a fruitful first source for exploring the Qur’an’s tacit worldview as well as the theology and moral themes that are expressed, hinted at, assumed, or nuanced in its individual texts and passages. These foundational worldview premises thread their way through the book, nuancing the meaning of the later and longer Sūrahs. The book’s early Sūrahs thus provide a philosophical backdrop of understanding to its subsequent passages, some which may appear to yield overlap of meaning with biblical thought—simply because they touch on similar themes of thought as the Bible, and yet, with subtle and profoundly divergent views of reality, God, and human beings.

At this step in the process, sound hermeneutical principles followed in biblical studies can be used to aid in the understanding not only of a specific qur’anic text on the micro level, but also its implications and meaning on the macro level as well. This includes word studies, semantics, historical/cultural contexts, and literary contexts as well as a chronological reading of the book to observe its theological development. As far as possible, the Qur’an must be allowed to be its own interpreter. The Qur’an must be read for itself, apart from Islam’s developed hermeneutical dependency on other sources of authority (the Hadith, Sira, Occasions, Tafsir, Shariah, etc.). One must allow for a kind of sola Qur’an, a “Qur’an as its own interpreter,” and a tota Qur’an, which asserts the fulness of its text to determine its meanings. Doing so allows the reader to observe patterns of thought and rhetoric and to sense the book’s own agenda and be guided by it.

In this process, qur’anic concepts together with their equivalents in both the Old and the New Testaments will then need critical comparison and analysis. The interpreter will observe more naturally the tension between qur’anic and biblical thought—sensing that on a surface level, at least, there is not much difference between their respective vision of God, human beings, moral accountability, and eternity. However, the seemingly similar spiritual/moral concepts and their ostensible agreement within differing worldviews and spiritual/moral contexts should not be assumed. Ultimately, the goal is the need to learn the language of the Qur’an and to learn how to reframe its issues and values within a biblical context so as to communicate Spirit-empowered biblical truth to a Muslim’s heart. This reframing relates more to the impact of the Qur’an’s worldview and theology on a Muslim’s heart than it does the details of these core values and truths themselves.

Ultimately, our Adventist understanding of the nature of biblical revelation/inspiration provides the hermeneutical context for determining the true nature of the Qur’an and how one relates to and utilizes the echoes of the biblical truth found therein. While we must allow the Qur’an to be its own interpreter and voice of authority, it is not the Adventist’s ultimate authority. All Scripture is inspired by God (2 Tim. 3:16, 17; 2 Peter 1:19–21). Scripture is its own interpreter (Luke 24:27, 44, 45; 1 Cor. 2:13; Isa. 28:10–13). It is the standard by which all doctrine and experience is to be tested (2 Tim. 3:16, 17; Ps. 119:105; Prov. 30:5, 6; Isa. 8:20; John 17:17; 2 Thess. 3:14; Heb. 4:12). Scripture provides the framework, the divine perspective, the foundational principles, for every branch of knowledge and experience. All additional knowledge and experience, or revelation, must build upon and remain faithful to the all-sufficient foundation of Scripture. The primacy of Scripture includes sola scriptura (the Bible only), tota scriptura (the totality of the Bible), and analogia Scripturae (the Bible is its own interpreter), and Spiritualia spiritaliter examinator (the role of the Holy Spirit in interpretation as spiritual things are spiritually discerned).

Thus, the biblical canon provides the hermeneutical context for evaluating both itself and everything beyond—including the Qur’an. There is need to uphold the Bible as the final and ultimate source of authority. It is the Bible that establishes that God takes the initiative in restoring all things back to Himself, and who reveals Himself in a multiplicity of ways and most perfectly through Jesus Christ. How the Qur’an and Islam testify to Scripture determines their ultimate credibility—especially as nuanced by numerous qur’anic deletions, additions, or abrogation of the biblical text, narratives, and truths, which are affirmed by Islam’s Hadith, Tafsirs, and Ulama (Isa. 8:20; 1 Thess. 5:19–21). Most importantly, how the Qur’an testifies to Jesus—to whom all Scripture points—likewise determines its ultimate credibility.

When it comes to biblical doctrine, we do not base our understanding on a single verse, or a couple of verses, for that matter. Nor do we allow an obscure verse to determine the meaning of something when other very clear verses reveal something different. Rather, we build understanding from many passages. We use simple, more easily understood verses to unlock the meaning of a difficult one. Biblical hermeneutics assumes the essential unity, coherence, and continuity of Scripture. Any so-called abrogation is unacceptable.

Qur’anic Christology

The Qur’an’s Christology can be summed up neatly in a single ʾāyah (verse): “O People of the Scripture [the Book]! Do not exaggerate in your religion nor utter aught concerning Allah save the truth. The Messiah, Jesus son of Mary, was only a messenger of Allah, and His word which He conveyed unto Mary, and a spirit from Him. So believe in Allah and His messengers, and say not ‘Three’ - Cease! (it is) better for you! - Allah is only One Allah. Far is it removed from His Transcendent Majesty that He should have a son. His is all that is in the heavens and all that is in the earth (Sūrah 4:171).”29

In addition to that of “Messiah,” three other designations for Jesus unfold from this defining qur’anic passage: Jesus was a “messenger” of God; He was God’s “word”; and He was “a spirit” from God. Elsewhere, the Qur’an refers to Jesus as “servant of God,” “prophet,” a “sign,” a “witness,” a “mercy” for us, an “example” or “parable,” an “eminent one” and “one brought near.”30 Jesus also is said to play a role in God’s plan following the future resurrection. But it is the designations outlined in Sūrah 4:171 that are the most prominent with regard to the Qur’an’s core Christology and are grist for Christian eisegesis. But as for the foregoing discussion of hermeneutics, the meaning of the individual names—“Messiah,” God’s “word,” and “a spirit” from God—is both defined and limited by the passage’s clear context and meaning. Their immediate (and larger) context disavows both Jesus’ divinity and His divine Sonship—and by extension the biblical doctrine of the triune God. This is the perspective from which we are to understand the Qur’an’s understanding of Jesus as “the Messiah,” “a messenger of God,” God’s “word” and “a spirit from” God.

First, this passage is directed to the People of the Book (in this context, primarily Christians) who are exhorted to speak only the truth about God and not to exaggerate things by ascribing divine status to their prophet Jesus. The verse thus “asserts the ur’anic view of Jesus as only a messenger of God, meaning a human messenger like Muhammad and the prophets who preceded him.”31 This is the obvious and plain meaning of the Sūrah 4:171 and its immediate/larger context.

The exclusive humanity of Jesus is further nuanced by the text’s designation that He is the “son of Mary” (Sūrah 4:171), a description “naturally taken to underscore Jesus’ true humanity: he is Mary’s son and not God’s.”32 The Qur’an refers to Jesus 25 times, referring to him in the Arabic name of `Īsā. On 16 occasions, the name `Īsā is found in combination with the descriptors “son of Mary” and/or “Messiah.” The phrase “son of Mary” is found 23 times in the Qur’an, either by itself or in connection with the name `Īsā, the Messiah, or the Messiah `Īsā. By intent, the Qur’an’s frequent use of the designation “son of Mary” underscores the mere humanity of Jesus, which is a central qur’anic theme. So also, the Qur’an includes an entire Sūrah titled Maryam (Sūrah 19) dedicated to Mary, the mother of Jesus. The focus on Jesus as the son of Mary is explicit denial of the incarnation and the mystery that “Jesus’ truly human existence is not short-circuited or compromised by the divine fullness indwelling him.”33

Second, this passage further distances Jesus from any notion of Sonship in relation to God: “Allah is only One Allah. Far is it removed from His Transcendent Majesty that He should have a son” (Sūrah 4:171). For the Qur’an, Jesus is clearly Mary’s son, and only so. He is not and cannot be God’s son at all. Surely, He cannot be both. This distancing of Jesus from any notion of Sonship in relation to God reflects the Qur’an’s vision of the unity of God as referenced above. The Qur’an’s judgment is that “it is not fitting for Allah to have a son” (Sūrah 19:35) and that the only proper mode of relation between God and Jesus is that of Creator and creature. Like any human being, Jesus was born, ate food, would eventually die, and in the eschaton experience resurrection life (Sūrahs 5:75; 19:33). As a human being, Jesus shares fully in creaturely existence. The Qur’an leaves the matter there. Anything beyond is considered shirk, i.e., associating something from creation with the uncreated deity in a way that compromises the divine unity and warrants a curse (Sūrah 5:73). The Qur’an rejects such ideas (Sūrah 5:17, 72–76) including that the Messiah could be divine (Sūrahs 5:17; 9:30).

These were the core truths that Christians presumably “exaggerated” or “disputed” (Sūrahs 4:171; 5:77; 19:34). It is not difficult to discern awareness and dismissal of Christian assertions about Jesus’ identity and nature, or of His mission and work. It is significant that the Qur’an does not offer anything near a biblical corrective. Rather it offers its own monotheistic assertions about the nature of God on the one hand, and on the other, a view of Jesus heavily influenced by non-biblical apocryphal literature.

Interestingly, Jesus occasionally receives in the Qur’an an even higher position than the prophet Muhammad. Given that some qur’anic statements describe Jesus as the “word of God,” “a spirit of God,” and even “Messiah,” it seems very intriguing and natural to examine these titles toward their intended Christological meaning. We need to ascertain to what extent is Jesus singled out in the Qur’an for special esteem, and why? To what extent does Jesus share the general esteem shown to all qur’anic prophets? Do the epithets applied to Jesus in the Qur’an—a “word” from God, a “spirit” from God and “Messiah”—denote a special place of honor on the prophetic rostrum, or are they simply rhetorical turns of phrase? Do they hint at something deeper—salvific, divine? Do they give tacit nod to biblical (Christian) nuancing/meaning? Finally, what is their origin?

Obviously, these descriptors (titles, epithets, appellations) provide incredible overlap with biblical vocabulary. But, do these common words convey common belief? Do they have similar meanings in their respective contexts? Is there a shared glossary from which the two scriptures draw? Do the titles convey or point toward the same intended Christology? Or, do the Qur’an and Bible’s contrasting core logic and metanarratives suggest an altogether different meaning and divergent Christology? Would their contrasting inner logic and metanarratives guide a respective reader’s perception and interpretation of these overlapping titles?

The Qur’an’s Christology thus affords the opportunity to explore the book’s core narrative on the one hand, and to provide an example of the implications of macro-hermeneutics in relation to our concerns about Christian eisegesis of the Qur’an on the other hand. As per above, the Qur’an’s core logic and narrative are fundamental to a more reliable textual exegesis and interpretation. But, what of its phenomenological parallels (words, terms, themes) with the biblical Jesus? Are they simply easy to misread as to their real or intended meaning? Or do they provide tacit invitation and justification for Christian backreading into the text in order to find common ground for inter-faith dialogue?

As shown above, in the same passage where Jesus is designated “Messiah,” God’s “word which He conveyed unto Mary,” a “messenger” and “a spirit from Him,” He is also clearly not in any sense of the word God’s “son.” Nor is He God in human form. Throughout the Qur’an, the divinity of the “Messiah” is categorically denied.

Beyond its phenomenological similarities with biblical terminology, this Christological passage (Sūrah 4:171) asserts a clear condemnation of core Christian beliefs about Jesus. It repudiates basic tenets of biblical revelation: that God is triune; the incarnation; Jesus’ relationship with the Father as Son. The literary context together with the Qur’an’s larger metanarrative places these appellations (“messiah,” “word,” “spirit,” “messenger”) within this defining and limiting context. The verse (Sūrah 4:171) refers to the three alleged persons of the Trinity, i.e., the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, and condemns Trinity, declaring Allah alone to be the one true God, and the Messiah and the Holy Spirit as only the servants of God and in no way sharers in Godhead.

The Qur’an’s very next Sūrah (5, Al-Ma‘idah) presents an understanding of the notion of a triune God that is not only at odds with orthodox Christian belief, but also presents Jesus Himself as denying His relation to God as Son, any notion of Trinity, as well as His incarnation (Sūrah 5:116, 117). While Jesus Himself is said to repudiate the notion that He is God’s Son, it is important to keep in mind that He allegedly does so in keeping with the Qur’an’s overarching metanarrative about God’s essential oneness and unity. Sūrah 5:109–120 asserts that there was nothing of Godhead about Jesus and that all material progress of Christians is due to their prayer to Him. In return, Christians have made improper use of the progress of God’s revelation—instead of believing in the Oneness of God, they believe in Jesus.

These Christological assertions do not reflect hatred or animosity toward Jesus, Christians, or Christianity per se. They do offer a corrective rebuke to Christians, however. Notions like Trinity and incarnation are at odds with the Qur’an’s fundamental assertion of God’s oneness and are therefore to be avoided. This is why, from a qur’anic perspective, Jesus clearly places Himself in a position of inferiority to God—to the place where He stresses God’s omniscience and asserts His own complete obedience to the divine will in relation to the matter of His Sonship with the Father and the Trinity: “I did not say anything to them except that which You commanded me to say” (Sūrah 5:117).

Jesus is thus “presented as a true believer [Muslim] who has submitted himself fully to the divine will and whose faith coheres with the message that Muhammad will deliver centuries later.”34 In effect, Jesus is the perfect Muslim whose life ultimately bears witness to the prophet Muhammad. The same chapter elsewhere asserts that only disbelievers (non-Muslims) would suggest that “God is the Messiah, the son of Mary” (Sūrah 5:17). They are confused. It further asserts that “there is no god save the one God” (Sūrah 5:73). No concept of a triune God or the divinity of Jesus is possible within the Qur’an’s overarching worldview of thoroughgoing monotheism.

The Qur’an’s denial of the divinity of “the Messiah” is unequivocal (Sūrah 5:17, 72). What understanding, then, does this description for Jesus convey for its readers?

The title “the Messiah/al-Masīḥ” is found 11 times in the Qur’an, always with the definite article, and in every case, it is used in reference to Jesus. While dozens of Arabic etymologies have been proposed for the word, it is most likely a simple borrowing of the biblical Hebrew term and its Christian use in relation to Jesus. However, the Qur’an does not provide a description of the role of the Messiah/al-Masīḥ, often considering it merely part of Jesus’ name rather than having anything to do with a particular role or a mission (Sūrah 3:45). Nor does it give a meaning for the title. It is possible that the title was adopted due to Christian usage of it without full understanding of its meaning. Nevertheless, the incorporation of the title “Messiah” into the qur’anic metanarrative effectively neuters its biblical missional, redemptive, and deific meanings. While the Qur’an utilizes terminology similar to its biblical counterpart, its macro-hermeneutical and epistemological context strips the concept of Messiah of its original biblical (and etymological) meaning. As Anderson notes: “Given the Qur’an never once describes what the Messiah is or does, we can only conclude that the term functions as an empty honorific.”35

What, then, of Jesus as God’s “Word”? Jesus is similarly described so in John’s Gospel, where He is presented as God’s “Word” that became human (John 1:1–18). So also, that for John, the “Word” is simultaneously identified with God (deity) and distinct from God (vss. 1, 2). The Word is the Creator who becomes human (vss. 3, 14). As Kaltner notes: “Although the terminology is the same, the Qur’an’s reference to Jesus/`Īsā as God’s word is different from that of the New Testament, where it is a way of speaking about Jesus’/`Īsā’s equality with God. Such a view would be inconsistent with Islam’s understanding of the deity.”36

Twice, Sūrah 3 refers to Jesus as “a word from God” (3:39, 45), but it conveys far less than what John had in mind in his Gospel opening. Sūrah 3 ends by stating that in God’s eyes, Jesus is in the same position as Adam who was animated by God’s word: “Indeed, the example of Jesus to Allah is like that of Adam. He created Him from dust; then He said to him, ‘Be,’ and he was” (Sūrah 3:59). As Adam came to life from dust by God’s word (“‘Be’”), God similarly spoke Jesus into being in Mary’s womb (Sūrah 3:45, 59). Jesus is thus a “word” from God—“‘Be’” (Sūrah 3:45, 47, 59). Sūrah 3:45 and 59 calls Jesus the Kalimah, i.e., a word from God. The verse denies the incarnation of Christ into human flesh because of the distinction that comes from the linguistic aspects in the Arabic language between “Jesus” and the “word.” As a proper noun, “Jesus” is masculine in gender, while “word” is feminine. Hence, since “word” is feminine gender, it cannot stand for “Jesus,” who is masculine. From that perspective, Muslim theologians see no difference between the creation of Adam and Jesus.

Sūrah 4:171 implies this when it says that the Messiah Jesus is “His word which He conveyed unto Mary.” If this interpretation is correct, the Qur’an’s reference to Jesus as “a word from God” relates to His coming into being rather than any specific role or position in relation to God or redemptive initiative.

Relatedly, Jesus is called a “spirit from God.” Here one is confronted with an interpretive choice—both exegetical and macro-hermeneutical. The question is not only whether the designation conveys a different sense than what it does for Christians when they read it in the New Testament, but whether it should be interpreted in connection with the Qur’an’s description of the conception of Jesus (Sūrah 4:169, 171) or its view of the supportive work of the Spirit in Jesus’ life (Sūrah 2:81, 87, 253, 254). The title “Spirit of God” is nowhere applied to Jesus in the Bible. Similar words however, are said about the creation of Adam—“I have formed him and breathed my spirit into him” (Sūrah 15:29)—which also recalls the biblical narrative where “The Lord God . . . breathed into his nostrils the breath of life” (Gen. 2:7). The Arabic term used in Sūrah 4:171 is ruh (“breath”)—a word that can, like with the Bible, often be mistranslated “spirit.” The exegetical and hermeneutical question is this: Which qur’anic meaning is intended? The implications are suggestive: “Just as a spoken word is one with the breath vocalizing it, so when God spoke Jesus into existence in Mary’s womb, Jesus was simultaneously that word from God and the breath conveying it. Jesus was thus animated by God’s breath, as was Adam.”37

It should be noted, however, that the Gospel record does associate the Holy Spirit with the conception of Jesus (Matt. 1:18; 20; Luke 1:35; 3:22), the baptism of Jesus (Matt. 3:16; Mark 1:11; Luke 3:22; 4:3, 9, 22), the temptations of Jesus in the wilderness (Matt. 4:1–11; Luke 4:1–13), the empowerment of Jesus’ mission (Luke 4:14, 18, 19), what constitutes blasphemy and Jesus’ power over the demonic (Matt. 12:22–32; Mark 3:20–30; Luke 11:17–23; 12:8–12), the sending of another Paraclete to testify of Jesus, glorify Jesus, teach truth, and be with the disciples (John 14:16, 17, 26; 16:7–11, 13–15), as well as the Great Commission (Matt. 28:18–20; Luke 24:44–49), and the disciples’ empowerment for mission (Matt. 28:18–20; Luke 24:44–49; John 20:19–23). In contrast to the Qur’an, which links spirit with a denial of sonship, each of these biblical passages affirms Jesus’ relation with the Father as Son (Luke 3:22; 4:3, 9, 22). They link together Jesus’ Sonship, servanthood, and divinity within the shared redemptive initiative together with the Father and the Spirit as part of the triune God.

With these observations in mind, the import of the Qur’an’s Christology, as summed up neatly in Sūrah 4:171, essentially negates meanings that any links with the Bible may seem to imply on the surface. The person and work of Jesus, while celebrated, are nevertheless marginalized and diminished. In particular, it is the Sonship of Jesus (with its tacit divinity implications) that is repeatedly denied.

It appears that the qur’anic Jesus is not the same as the biblical Jesus and that the differences are hard to reconcile. “Despite the deep reverence in which Jesus is held in the Qur’an, certain core truths that are applied to Him in the Bible are explicitly denied.”38 “Jesus is a controversial prophet” whose presence in the Qur’an is “embroiled in polemic.”39 He is emphatically not the Son of God, not part of a divine trio. The Qur’an emphatically refutes such. He is called `Īsā (rather than Jesus), son of Mary—implying that He is merely human. Very much flesh and blood.

Furthermore, the Christian concept of redemption is absent. Jesus did not die as a substitute for sinful human beings. Jesus is nothing more than one of God’s messengers, one of the prophets. He is singled out with special esteem while at the same time sharing the general esteem shown to all qur’anic prophets. He confirms the revelations preceding Him. He is the last prophet before Muhammad who brings good news of the messenger who would follow him—Muhammad (Sūrah 61:6). As such, Jesus is not God’s final revelation. He is a perfect Muslim. True followers of Jesus will eagerly follow Muhammad (not the opposite). It seems that it is the ascension rather than the crucifixion that marks the high point of Jesus’ life in the Qur’an.

Yet, in spite of all this, the Qur’an piles more honorific titles on Jesus than on any other prophet apart from Muhammad. At the same time, it flatly denies Jesus’ divinity and limits Him to prophethood. It grants Jesus the biblical title of “Messiah,” but minus its biblical meanings. It reflects the Qur’an’s two-stage approach to Christology: the project of the “deconstruction and reconstruction of Christ’s identity.”40

Additionally, the Qur’an possibly allows for Jesus’ death as historical, but negates any sacrificial, redemptive purpose, and greatly marginalizes the event so central to the New Testament Scriptures. Ultimately, it is “not so much the doctrines of the Trinity, Christ’s sonship, or his divinity, in and of themselves” that the Qur’an negates, but rather “the connection of these doctrines with the understanding of salvation.”41

No matter how highly the Qur’an or Islam places Jesus, His person and His work are either diminished or marginalized. His role as the final Word of God to human beings is essentially negated. It is not inconsequential that within 60 years of Muhammad’s death, that key qur’anic inscriptions on The Dome of The Rock in Jerusalem unequivocally deny the deity and redemptive work of Jesus Christ.

The Qur’an presents a devout John the Baptist who endorses Jesus and presents Him as sinless in order to establish the sterling credentials on which His unqualified backing of Muhammad rest. John’s story in the Qur’an points to his spirituality and his endorsement of Jesus (Sūrah 3; 19).

Mary is highly honored in the Qur’an (Sūrah 3). The most common reference to Jesus is “son of Mary.” This points to: Jesus’ noble origins, Jesus’ miraculous birth, and Jesus’ non-divinity, for having a mother means he cannot possibly be God. In the Qur’an, the human and divine are mutually exclusive categories. If Jesus is the son of Mary, He is not and cannot be the Son of God. In the end, the Qur’an carefully limits Jesus’ stature in order to assure that He does not eclipse Muhammad.

The larger biblical cosmic conflict macro-hermeneutic is helpful as we reflect on qur’anic Christology and what it says about Jesus. The person of Jesus has been at the center of the cosmic conflict since it began in heaven. Scripture proclaims Jesus as the final revelation of God (Heb. 1:1–4). “‘If you have seen me, you have seen the Father,’” Jesus asserted (John 14:9). Christ’s Sonship is core to the biblical perspective of truth in relation to the spirit of antichrist. According to biblical prophecy, history will climax in the universal worship of Jesus: “at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (Phil. 2:10, 11, NIV).

And so, we wonder, what (if any) redemptive analogies can serve as bridges with respect to the person and work of Jesus? Can qur’anic assertions about Jesus be made to mean something different from the Qur’an’s own intent and overarching metanarrative?

The Qur’an was likely responding to a myriad of Christian heresies, and its vision of Jesus was an intended corrective of Christian heresies—howbeit a naïve and inadequate corrective. This includes the Qur’an’s use of the term `Īsā for Jesus as well as Nasara for Christians.

No matter the meaning of some qur’anic texts regarding the death of Jesus (did it happen or not?) or how Jesus was received into heaven and when, there is both an underlying denial of any substitutionary death with regard to human need of redemption and salvation, and there is a denial of Jesus’ divinity and incarnation. No matter how much one may nuance certain passages (āyāts) to finesse implications toward affirming Jesus’ divinity, said allusions must be read within an overarching worldview and theology that denies such. It is not just a matter of the right understanding of a particular qur’anic word or phrase or āyāt in its immediate context. “Rather, one must consider the topic against the background of the entire Christology of the Qur’an.”42

This understanding is our starting point when using the Qur’an in dialogue with Muslims. It informs us how to better use the Bible as we bridge to the human need and existential angst of the Muslim soul. If we begin with the assumption that the Qur’an affirms the divine Sonship, deity, death, or redemptive work of Jesus in any capacity, we will not be able to fully grasp how deep the need a Muslim has or how direct we may need to be in uplifting the Savior (as first-century believers did).

Summary and Conclusion

This study begins with the question of whether or not the Qur’an contains redemptive analogies that could be used as bridges to present biblical faith. It asks whether the Qur’an’s direct and tacit subversion of the essential elements of the gospel might deny such and/or actually press Christian gospel workers to better present biblical truth and faith. To answer these questions, we must first think biblically about the Qur’an. This does not mean reading of the Qur’an through biblical eyes in order to unfold biblical gospel themes from the Qur’an for Muslims. Rather, it is thoughtful and critical, biblical engagement of the Qur’an’s “inner logic” system on the macro-hermeneutical level in order to better use the Bible in gospel work among Muslims. There is little doubt that a deeper familiarity with Muslim scripture holds out the prospect of better communicating the gospel. A macro-hermeneutical-level understanding of the Qur’an is critical in relating meaningfully to Muslims whose worldview and daily life have been indelibly shaped by the Qur’an and its ethos.

Toward this goal, we have explored four aspects of the Qur’an in relation to the Bible: its self-image, worldview, hermeneutic, and Christology. In doing so, we have assumed that the Qur’an exhibits a “core logic” and that its “inner system” inevitably affects the understanding and interpretation of its individual verses as well as its overall meaning. If the Qur’an has no core logic or inner worldview system, then its text is open to the confusion of multiple meanings and interpretations, including Christian eisegesis.

An exploration of the Qur’an’s Christology—summed up neatly in Sūrah 4:171—affords the opportunity to explore the book’s core narrative and inner logic on the one hand, and to provide an example of the implications of macro-hermeneutics in relation to our concerns about Christian eisegesis of the Qur’an on the other hand. So also, we gain a clearer understanding of worldview realities that pulse within a Muslim’s inner world.

In the process of this study, two critical concerns of gospel work among Muslims are informed: the position and status of the Bible in relation to the Qur’an on the one hand, and the person and work of Jesus on the other. Clarity of what the Qur’an does or does not say on these two issues inevitably determines the kind of bridge one can and/or needs to create. How can the Qur’an be a divine book if it diverges from the biblical worldview, together with its Christology? An understanding of the Qur’an’s core logic and worldview narrative is fundamental to both a more reliable textual exegesis and interpretation of the Qur’an as well as the existential realities, that the qur’anic worldview and rhetoric stirs within a Muslim’s soul.

In order to use the Bible wisely and effectively, the gospel worker needs an accurate, clear understanding of the Qur’an and the worldview it reveals, reflects, and validates. The macro-hermeneutic must inform the micro-hermeneutic. Because the differences between the biblical and qur’anic worldview are substantive (but often blurred), there is need for sound interpretive principles that will allow the Qur’an to speak for itself. The failure to do so—to inadvertently or consciously insert biblical meanings into qur’anic passages—i.e., eisegesis—is to run the risk of compromising the biblical message that the Muslim listener needs the most. Such a compromise is often created by:

● Assuming that the two texts are expressions of the same divine revelation, thus positioning the Qur’an to affirm the Bible or vice versa.

● Assuming the qur’anic message is sufficient to meet the inner needs of the Muslim believer.

● Failing to introduce aspects of the contrasting, biblical worldview for the Muslim listener to consider.

● Underestimating the high impact of the Bible alone in meeting the needs of a Muslim’s heart, regardless of his or her belief system.

● Losing the opportunity to share the Bible with the Muslim listener through one’s living witness, which the Holy Spirit can utilize in his or her spiritual journey.

By positioning the Bible and the Qur’an alongside each other as two “holy books,” or two forms of a “Word from God,” the tendency exists to unwittingly assume similar meanings and intent behind the texts and to conclude that the message of the Qur’an is conceptually similar to the Bible. The end result is: (1) to arrive at an indistinct understanding or misreading of the Qur’an for itself; (2) to assume that the qur’anic worldview is similar to the biblical worldview; and (3) to be incapable of articulating the biblical message with the level of worldview implications, conviction, and practicality that the listening Muslim deserves.

Ultimately, our goal is unfolding gospel themes from the Bible for Muslims—and to do so in a relevant way. That is best accomplished when the interpreter understands the Qur’an’s core logic. In doing so, he or she can better imagine the existential impact that the Qur’an’s worldview has on the Muslim soul. Christians will not know how to use the Bible most effectively in Muslim contexts until they understand the deeper soul need of a Muslim as nuanced by his or her exposure to the Qur’an—its worldview and ethos. This is a fundamental starting point for mission. It requires a deeper understanding of the Qur’an than what biased eisegetical and proof-text approaches—which manipulate the text for missional purpose—can enable. A sound, biblically informed macro-hermeneutic, which facilitates such deeper understanding of the Qur’an, is essential. It also necessitates a deeper understanding of the Bible on its own macro-hermeneutical and worldview level.

The concern here is not whether to use the Qur’an in gospel work in Muslim contexts. That is a given. Rather, we ask: Why do we use the Qur’an? When do we use it? How do we use it? More importantly, do we allow the Qur’an to speak for itself, or are we manipulating the text via Christian qur’anic eisegesis? If we do use the Qur’an, in what way or on what level should it be advanced as an authority? Is it ethical to create redemptive analogies/bridges from qur’anic phrases and texts that were never so intended in either their immediate context or the Qur’an’s core metanarrative?

Relatedly, how can we nuance corresponding biblically relevant theological or soteriological themes from the Qur’an without implying that it authoritatively affirms those truths? At issue are these questions: What hermeneutical and ethical guidelines are we bound to when handling Islam’s holy text? Are we aware of our limits in doing so? The Qur’an itself is limited in its ability to meet the kinds of inner need Muslims have in relation to the grand themes and issues of the biblical cosmic-conflict metanarrative.

But our opening questions remain: (1) Does the Qur’an contain redemptive analogies that can be used as bridges to present biblical faith? and (2) Does the Qur’an’s direct and tacit subversion of the essential elements of the biblical gospel actually press Christian gospel workers to better present biblical truth and faith?

We return to these questions now, knowing that the Qur’an is positive toward both Jesus and what we today call the Bible. Qur’anic conversation with the Bible remains of current interest in Muslim contexts. The question of what missional bridges exist between the meaning of the Qur’an’s teachings and the truths of the Bible is relevant and pressing.

Our exploration of qur’anic worldview and Christology suggests that numerous terminological and conceptual links do exist between the Qur’an and the Bible, i.e., words, phrases, terms, biblical characters, as well as broad moral, spiritual, and theological matters. We could list the person of Jesus, the title “Messiah,” bodily resurrection in the eschaton, eschatological judgment, sanctity of life, God as Creator, human nature, the existence of evil, Abraham’s sacrifice of his son and God’s provision of a lamb, etc. Some of these may be more conceptual bridges than the kind of redemptive analogies we desire. Yet they offer a place to begin. Furthermore, these varied possibilities reflect only parallels rather than the kind of deeper core-level meanings that would yield real substance to any bridging concept or create significant redemptive analogies. These conceptual links, however, do potentially provide significant points of contact that can open the door for deeper exchange.

While, as we have seen, the Qur’an unequivocally and uncompromisingly rejects the Sonship and deity of Jesus, it nevertheless holds Jesus in high esteem. Accordingly, Muslims in general have a strong attraction to Jesus. Even the Qur’an’s incomplete and marginalizing picture of Jesus seems to whet the appetite of Muslims to know more. This in itself affords an incredible bridge and opens the way toward redemptive implications. Ultimately, it is the more complete picture of Jesus in the Bible that seems to captivate and lead Muslims across the bridge to a worldview shift.

The Qur’an’s descriptor of Jesus as “Messiah” further nuances these possibilities for deeper understandings of Jesus and potential redemptive analogies. While based on entirely different conceptual frameworks and meanings, the title “Messiah” is nevertheless terminology shared by the Qur’an and the Bible. It offers one of the strongest points of reference for deepened conversation. The challenge for Muslims comes in unlearning qur’anic concepts (or lack thereof) behind the title and learning biblical ones. Ultimately, it is the Bible’s more complete picture of what the title “Messiah” means that becomes critical.

Obviously, there are other qur’anic referents to Jesus that could become redemptive analogies: the uniqueness of His birth, His involvement with God in eschatological realities (resurrection, judgment), etc. But again, the truth about these realities is found only in the Bible, not the Qur’an. The Qur’an merely provides a referent that allows for engaging deeper conversation. We might ask, what is the meaning of the title “Messiah”? Was it Isaac or Ishmael whom Abraham was willing to offer? What redemptive analogies are possible in the narrative of God’s ransoming Abraham’s son with a “momentous sacrifice” (Sūrah 37:107)? Any redemptive meaning of these links comes through the biblical perspective alone. The gospel worker’s familiarity with the Qur’an enables such conversation and biblical enlargement.

A worldview macro-hermeneutical-level perspective is essential when relating to the Qur’an and its intended meaning. No matter what individual qur’anic texts may seem to say or affirm on a phenomenological level with reference to possible bridging concepts with the Bible, the qur’anic worldview and macro-hermeneutic must be allowed to dictate the understanding of their real meaning. The macro-hermeneutic must inform the micro-hermeneutic. Again, we cannot know how best to use the Bible as a bridge to lead a Muslim to the Bible unless we first understand just how unbiblical and marginalizing of the person and work of Jesus and His relationship with the Father the Qur’an really is. We will not know how to use the Bible more effectively until we understand the real need of a Muslim who lives and breathes the qur’anic worldview. This understanding of the Qur’an’s core logic and worldview narrative is fundamental to a more reliable textual exegesis and interpretation. It is a fundamental starting point for mission in Muslim contexts. With it is the similar need for a deeper understanding of the Bible on its own macro-hermeneutical and worldview level to know how best to use it to lead Muslims to the Bible.

Missiological Implications

Finally, what missiological implications might arise from the four themes highlighted—qur’anic self-image, worldview, hermeneutics, and Christology? The following reflections are meant for the gospel worker’s consideration and praxis, not for the Muslim. It is assumed that any approach must come from the viewpoint of values and truths that unite rather than denounce and offend. These shared values/truths can provide windows into a Muslim’s heart and open the way for deeper conversation.

Self-Image: Awareness of the Qur’an’s self-image provides a clearer understanding of how biblical progressive revelation/inspiration operates by contrast. This awareness can clarify questions regarding the Qur’an’s asserted inspiration and dominance as well as why it remains so embedded as an authority within the Muslim’s worldview. It can inform, too, how and when one might best use the Qur’an in conversation with a Muslim. It invites Christians to saturate their own imagination with biblical truths and values that can then flow naturally from their lips and may influence their personal life. This includes an intimate witness of a personal God whose character is love. This “Word and witness” can unfold spontaneously and effortlessly and in a way that can touch a Muslim’s heart and awaken his or her interest in what more the Bible might have to give beyond the Qur’an. The question is: What do we reveal in our own life and character about the person and character of Him? How freely do we speak of Him and in what way? What do we need to better understand God in order for our witness of Him to be more life-changing both for ourselves and for those to whom we speak of God? Can we speak of our God as freely and joyfully as it appears some of our Muslim friends do? Will we ever be able to build credible bridges unless we we have such an exalted vision of God that enables us to capture a Muslim’s imagination and heart in an area of which they are already well versed?

Worldview: How the Qur’an’s monotheistic worldview centers Muhammad in relation to both God and itself provides insight into the Qur’an’s inner logic and core emphasis. One can understand better the eclipsing position Muhammad holds in a Muslim’s imagination. This is a reality not to be directly challenged, but nevertheless understood in relation to the person and work of Jesus Christ as asserted in the biblical worldview of the cosmic conflict. Furthermore, noting the tacit Platonic philosophical influence reflected in the Qur’an’s monotheistic vision of God can enable one to better understand the role that God plays in a Muslim’s faith experience: i.e., what God is rather than who God is, transcendent/unknowable rather than immanent/personal, knowable. It should be remembered that while, theologically speaking, the God of the Qur’an (or Islam) may not be personal, the people of Islam are personal and envision Him as such.

Understanding the Qur’an’s tacit Platonic backdrop also enables more informed exegesis of qur’anic verses that touch on the nature of man, death, resurrection, the jinn, eternal punishment, etc. Further noting how the Qur’an—together with the prophet Muhammad’s own religious practice—foster a spiritual cosmology, which inadvertently encourages a folk Islam experience, can facilitate a deeper understanding of some of the existential burdens and fears that a Muslim may carry. This tacit animism—belief in spiritual beings, practices, sacred objects, talismans, times or places capable of helping or harming human interests—nuances a sense of power/vulnerability, control/fear in keeping with the piety of a Muslim’s devotion and religious practice and experience. All the more, there is need to help a Muslim experience the biblical understanding of the fear of God, which eschews the fear of all other asserted or imagined powers (Ps. 34:4, 7–9; Rev. 14:7).