Mission needs to be the driving force for the church’s desire for unity

Gerald A. Klingbeil

Unity has become a particularly appealing concept in our economically, socially, and politically fragmented world. In the face of huge global challenges, we hear people ask, How can we survive and even thrive if we do not work together?

With Christianity stagnating or even in decline in many parts of the world, the idea of Christian unity as a means of meeting the tremendous challenges to evangelism and growth has been the focus for many denominations. Advocates for increased ecumenical relations (and the need for Christian unity) are quick to quote Scripture: “‘My prayer is not for them alone. I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message, that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me’” (John 17:20, 21, NIV).1

These verses are crucial for the current topic and require a closer exegetical look. John 17:1 clearly underlines the prayer framework of the chapter. Yet, packaged as part of this prayer, John 17 represents one of the longest teaching sessions of Jesus in Scripture, associated with the Last Supper. A close reading of the biblical text suggests that Jesus was worried about what He knew was soon to take place. Jesus knew that He was about to be delivered into the hands of His enemies, that His divided followers were not ready to face the next hours. He felt the weight of sin pressing on His heart. As Jesus prays, He also teaches. There is a clear sequence in the prayer, covering Jesus’ own relation to the Father (vss. 1–5), followed by specific prayer for His disciples (vss. 6–19), and finally looking into the future and praying more generically for future believers (vss. 20–26). The call for unity appears throughout the prayer in different forms, but is most explicit in verses 20 and 21.

Jesus’ concern for unity must have been triggered by noting the sense of disunity among His followers. No one had stood to wash the feet (John 13) and many references in the Gospels point to the repeated discussions among the disciples concerning leadership, control, and greatness (Mark 9:34; Luke 9:46; 22:24). Was this the group that God had to rely upon in bringing the gospel to all the world? Jesus prayed for “all” who would come to believe in Him, including future followers of Christ (and, therefore in this particular context, not all the world). He anchored this unity in the unity between the Father and the Son—the Trinity. The unity of His followers was to be based on a common foundation (“‘be onein us’”) and would have a surprising effect: When the “world” (that is, the people) would see this unity in purpose and mission, they would believe that Jesus was truly sent by the Father (and thus one with the Father) and the Savior of the world. In summary: Jesus’ call to unity is driven by mission and is truly radical, as noted by George Beasley-Murray: “It [the unity that Jesus refers to] is rooted in the being of God, revealed in Christ, and in the redemptive action of God in Christ.”2

Historically, the idea of Christian unity had a missiological focus and clustered around the desire to bring Christ to all the world. Fast forward, and we note that the missiological focus was replaced by the desire to accomplish unity, or, in the words of an official document of the World Council of Churches, “a growing number of voices from the churches, especially in Asia but also in Latin America, have spoken of the need for a ‘wider ecumenism’ or ‘macro-ecumenism’—an understanding which would open the ecumenical movement to other religious and cultural traditions beyond the Christian community.”3

This study will keep in view both the larger attempt at ecumenical relations (or “macro-ecumenism” as it is called in the above quote) as well as the more familiar interdenominational Christian dialogue. In both instances, the desire for unity and understanding seems to be the driving force, showing a significant departure from the drive for Christian world evangelism that marked ecumenical relations and ecumenical mission conferences of the late 19th century. This shift has also been noted by many authors documenting the change from the “Christocentric universalism” that the first general secretary of the World Council of Churches (WCC) postulated to the understanding of the Greek word translated as the “one household of life.”

I would like to return to the biblical foundation for the quest of unity, discussing relevant biblical data because Scripture’s inherent truth claim as the only standard of faith and practice needs to drive theological (and other) thinking of Seventh-day Adventists around the world. Echoing other academic research, the biblical “soundings” will hopefully provide a direction or guide for discovering important underlying principles that are relevant to ecumenical relations in the 21st century.

“Back to Babel”: The Community Project That Divided

Leaving aside for a moment the unity of husband and wife as portrayed in the creation narrative in Genesis 1 and 2, probably one of humanity’s first post-Fall attempts to work together in a coordinated manner is recorded in the Tower of Babel narrative found in Genesis 11. The biblical text highlights in Genesis 11:1 the fact that the anonymous builders had one language and one speech—which sounds like a lot of common ground, avoiding misunderstandings due to linguistic (and consequently cultural) differences or even nuances. The pivotal point of the chiastic structure of the story can be found in verse 5 when God comes down to “see the city and the tower that the men were building.” God’s negative reaction at this attempt of human unity is clearly expressed in the divine dialogue. “‘If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them’” (vs. 6). This is the final diagnostic. What element of this attempt at unity could God have found so threatening?

The Tower of Babel narrative does more than highlight the power of human communication. The anonymous human participants of the story speak repeatedly about the need to build a city and a tower—most likely a ziggurat-like temple structure reaching to heaven (vss. 3, 4)—and the desire to “‘make a name for ourselves’” (vs. 4). Sailhamer notes that, to “make a name” is a phonetic wordplay with the name of the godly son of Noah, Shem.4 It also anticipates the divine promise to Abraham in Genesis 12:2—“‘I will make your name great’” (i.e., you and your descendants will be renowned and highly esteemed). In this sense, “making a great name” is a divine prerogative and not the result of human design and effort. The tower builders are not only trying to erect a structure reaching heaven, they also intend to do so through their own efforts, and openly defy the divine command to “‘be fruitful and increase in number and fill the earth’” (9:1). Human hubris is countered by divine judgment, not because God does not like towers or cities. Rather, the builders’ attempt to usurp divine attributes and prerogatives through united coercive action lies at the heart of this swift divine response.

Scripture seems to fault the ancient tower builders on two accounts: their lapse of a sense of God’s mission—which, at that time, was to spread out and fill the earth—and their attempts to do things their own way, highlighting the danger of manmade attempts at unity.

“Familiar” Beginnings

Even in a postmodern and genuinely fragmented world, families remain as important building blocks of society—although the notion (or institution) of family is under attack. In the Old Testament world, families were even more important. Any attempt at unity would begin with the integration of families.

The call of Abraham involved the call of a family, which by faith had yet to be. God’s call is exclusive (Gen. 12:1) yet inclusiveness is emphasized (vs. 3). Abraham’s (often dysfunctional) family were called to be different and custodians of the promise—yet, ultimately, they were called to mission and become a blessing for the tribes and people living around them. In Abraham’s case, this meant leaving his father’s home and country and going to an unknown land where he was to remain a “stranger” and not to assimilate with the local tribal groups, even though we find the patriarch at times collaborating with neighboring clans and people. When Isaac became of marriageable age, the fear of assimilation (or absorption) with the local population groups led Abraham to send his servant Eliezer to find a wife for Isaac from his clan and not have him intermarry locally (Genesis 24). Even though Nahor’s descendants in Syria apparently had their own struggles in relating to YHWH, Abraham felt compelled to find a wife for the son of the promise, Isaac, within his clan, due to their relationship to YHWH. The biblical authors repeatedly emphasize the fact that distinct religious loyalties and values were the key distinguishing factor, since the tribal groups spoke similar (Semitic) languages, practiced similar lifestyles (often preferring a semi-nomadic lifestyle), and shared in some instances also comparable cultural characteristics (e.g., importance of family and clan, power of elders, etc.).

Further on in the Pentateuch are explicit legal data concerning the marriage of Israelites with non-Israelites (Deut. 7:1–10). Looking forward to Israel’s increasing interaction with foreign nations, including the Hittites, the Girgashites, the Amorites, the Canaanites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites (vs. 1) during the settlement period, there was a need for clarifying the prior order to execute the “ban” on these people groups (as, for example, ordered in Numbers 21:2, 3). As has been argued elsewhere, the complex issue of the ban not only entailed military or socio-political connotations, but also involved definite religious and ritual implications.

In Deuteronomy 7:2 and 3, the text highlights the fact that banning these tribes meant practically that Israel should not enter into a covenant relationship with them. Furthermore, Israel was not to give their sons and daughters in marriage, nor should they seek marriage partners from these groups for their children (vs. 3). The rationale provided by the text is simply that “‘they will turn your sons away from following me to serve other gods, and the Lord’s anger will burn against you and will quickly destroy you’” (vs. 4). It would seem that unity with these nations through intermarriage would come at the price of Israel’s unique mission and would involve giving up the truth about the worship of the only true God—even though the issue is not always clear cut.

The list of known cross-cultural marriages in the Hebrew Bible is quite extensive. Interestingly, the biblical text includes both positive and negative evaluations of specific cross-cultural marriages. Some positiveexamples include Rahab and Salmon (according to the genealogy of Matthew 1:5), Ruth and Mahlon/Chilion and later Boaz, while negative examples comprise, for example, Solomon and Pharaoh’s daughter (1 Kings 3:1) or Ahab and the Phoenician princess Jezebel (1 Kings 16:31).

What particular element made the difference in the evaluation of the biblical authors? This question may be rephrased in the particular context of this study: What would make unity or ecumenical relations acceptable in Old Testament marriage terms?

Psalm 45 may provide an interesting take regarding acceptable cross-cultural marriages against the backdrop of a royal marriage scenario (perhaps during the time of Solomon?) and the associated status of foreign wives (or queens). Commentators have entitled this psalm as a royal wedding song, and verse 11 [English vs. 10] is highly relevant for this discussion: “‘Listen, daughter, and pay careful attention: Forget your people and your father’s house.’” The admonition to forget both family and the “‘father’s house’” suggests not only cultural or sociological reorientation but must have also involved religious loyalties. In this sense the ideal for any king marrying outside the tribal group involved a reorientation of the future queen’s loyalties, including also her religious affiliation.

The Old Testament data concerning cross-cultural marriages seems to emphasize that integration, or unity, is positive only if it does not come at the expense of recognizing YHWH as the supreme Deity or sacrificing the truth claims of a “Thus says the Lord of Israel.” God’s special mission for Israel as His people was not to be surrendered.

Unity Between Brothers

A closer look at relationships (and unity) among different subgroups of Israel (the 12 tribes) as well as groups that were somewhat related to Israel (the Ammonites, Moabites, and Edomites) may better reflect the closer relationship of modern Christian denominations.

The biblical picture of tribal relations in Israel is complex. Beginning with the often-convoluted interaction of Jacob’s 12 sons described in Genesis 37 to 50, the biblical text shows fissures that continuously undermined or even threatened the unity of Israel’s tribal system. Sociological and anthropological research has demonstrated the complexity of tribal societies whose members had to balance family and clan loyalties with the commitment to the tribe, and should not be confused with the modern notion of a nation and loyalty of citizens to the state. In the context of the Old Testament, leadership issues (and the status of the firstborn) made family and tribal relations even more complex. Not surprisingly, there are a number of instances in the Old Testament in which the eldest (or firstborn) loses his leadership prerogative. Most research dealing with these inversions focuses on theological reasons—and theology is definitely significant in this context. The upheaval of well-established (even divinely ordained) lines of leadership always highlights God’s prerogative of divine election—yet at the same time does not necessarily represent divine rejection.

During the period of the judges, tribal alliances shifted constantly. External threats (or enemies) at times united some tribes, while other unaffected tribes (often separated by geography and location) did not get involved. As has been noted by Webb, “the essential bond between the tribes was their common history and their allegiance to Yahweh. He himself was their supreme Ruler or Judge (Judges 11:27), and his law was their constitution.”5 Apparently the key constant unifying factor that kept Israel’s tribes together was the Tabernacle and Yahweh worship enforced by charismatic leaders. While the prologue of the Book of Judges portrays Israel as a unity and suggests a national or unified perspective, the book’s central section describes less the ideal but more accurate the reality of intertribal conflict, often associated with blatant idolatry or the more subtle religious syncretism.

In the early united monarchy Benjamin (under Saul) and Judah (under David) were at times pitted against each other. External threats continued to unite the tribes until David, following his coronation by all 12 tribes, finally succeeded in establishing Jerusalem as the new capital (2 Sam. 5:6–12). The fact that the city had not been under the authority of any Israelite tribe was part of David’s genius. Furthermore, as the coronation narrative at Hebron amply illustrates, David’s divinely appointed kingship and the kinship between the individual tribes was clearly recognized in the offering speech of the 10 northern tribes (vss. 1–5). Following the heydays of David’s and Solomon’s rule, the 10 northern tribes separated from the two southern tribes and their Davidic dynasty (1 Kings 12), resulting in the establishment of two kingdoms, Israel and Judah. The following 200 years witness numerous military encounters between the two kingdoms, while at times coalitions between the reigning royal families meant limited periods of peace. God’s prophets were sent to both kingdoms, even though northern Israel had engaged in the idolatrous worship of calves that had been established by Jeroboam I in Bethel and Dan (vss. 25–33). Divinely approved engagement between the kingdoms seems to have been predicated on religious reform and a common commitment to the Torah and the prophetic word that highlighted the law.

The complex and convoluted relationship among the 12 tribes of Israel provides the backdrop for the even more complex and often antagonistic relationship between Israel and the surrounding tribes (including Moabites, Ishmaelites, Edomites, Ammonites, etc.). The close relationships to these tribal groups are repeatedly highlighted in Genesis (Genesis 16; 19:34–38; 21:8–21; 25:12–18; 36).

All four tribal groups had kinship links to Israel, yet interaction between Israel and these tribal groups suggests not only disunity or indifference, but also at times plain hatred and animosity. Edom is subjugated by Saul and David (1 Sam. 14:47; 2 Sam. 8:13; 1 Kings 11:15, 16), but rebels later against Judean control (2 Kings 8:20–22) and is repeatedly mentioned in prophetic texts (Amos 1:11, 12 notes Edom’s fury and lack of compassion). Psalm 137:7 suggests that the Edomites rejoiced over Jerusalem’s destruction. However, at times YHWH is portrayed as coming from the region of Edom to aid Israel (Deut. 33:2; Judges 5:4; Hab. 3:3). Similarly, Israel’s relationship with Moab was also characterized by conflict (Judges 3:12–20; 1 Sam. 14:47; 2 Sam. 10:1–14; 2 Kings 3:1–27; etc.), with Israel subjugating Moab during the united monarchic period. Interestingly, Moab provides also a refuge for those fleeing a famine in Bethlehem (Ruth 1), and a Moabitess (Ruth) becomes part of the genealogy of David and—ultimately—the Messiah. Yet biblical law forbids the inclusion of Moabites and Ammonites into the assembly of Israel (Deut. 23:3–6). The tension points up the importance of religious commitment. Ruth’s powerful poetic confession, “‘Your people will be my people and your God my God’” (Ruth 1:16) highlights the significance of the commitment to the God of Israel—on YHWH’s terms.

The preceding comments have highlighted the highly complex biblical picture of intertribal relations within Israel as well as with surrounding people groups during different times of biblical history. Crucial to interaction and positive engagement was Israel’s faithfulness to the divine commands as well as its ability to resist syncretistic tendencies—both from within and without. Though modern Christian denominations (or even world religions) cannot just be equated to the tribal realities of ancient Israel within the landscape of the ancient Near East, the importance of faithfulness to the revealed “Word of the Lord” and the devastating effect of syncretism within the covenant people throughout their history suggest careful evaluation when considering modern ecumenical relations—both on the macro-ecumenical, but even more on the micro-ecumenical level.

Unity and the Schism Between Jews and Samaritans

The often-strained relationship between Judaism and Samaritans, hinted at in the postexilic texts of Ezra–Nehemiah, provides another useful location for a sounding that may be relevant for the nature of ecumenical relations in the 21st century within the larger body of Christian denominations. The basic history of the Samaritans as a religious group showing homogeneity and shared beliefs is problematic. Samaria, the capital of the northern kingdom during the divided monarchy, had also been the center of religious diversity. Israelite kings were seldom known for their orthodoxy, and the installation of calves in Bethel and Dan by Jeroboam I (1 Kings 12:26–33) should be considered a conscious break with the religio-political establishment in Jerusalem.

In fact, following the canonical sequence of the biblical text, the earliest reference to specific religious syncretism can be found in 1 Kings 17:24 to 41 in connection with the resettlement of Samaria following the Assyrian destruction of the city and the complete absorption of Israel into the Assyrian empire. Josephus’ description of the event echoes this biblical statement. Interestingly, the self-understanding of their origins in Samaritan sources claims that the group originated in the 11th century B.C., during the time of the judges and relates it to the establishment of the cult/tabernacle at Shiloh, which was established (so suggest the Samaritan sources) in rivalry to long-established Shechem. In this sense, Samaritans (or Israelites, as they preferred to call themselves) recognized only the Pentateuch as the inspired Word of YHWH and claimed orthodoxy going back to the premonarchic period.

The Old Testament, however, underlines the marginal nature of Samaritan worship and chronicles conflict during the Persian period. The opposition to the reconstruction of the temple and its city is linked to Samaria (Ezra 4:7, 8, 17). During Nehemiah’s period of leadership, Sanballat the Horonite is one of the key opponents (Neh. 2:10, 19) of the reconstruction effort and is closely associated with Samaria (4:1, 2; 6:1–14). Even though the specific nature of the tension between the Jewish returnees and the Samaritans is never articulated, its existence cannot be ignored. Later Samaritan sources highlight theological discrepancies, such as the inspiration of the Pentateuch versus the entire Hebrew Bible. Clearly, there was not much common ground between Samaritans and Jews, and the attitude of Jews living in New Testament times (including also the disciples) toward Samaritans was one of rejection, hatred, a sense of superiority, and complete separation.

Jesus’ paradigmatic encounter with the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well (John 4:1–42) provides an intriguing example of how Jesus dealt with those who were considered outsiders. Suffice it to say that Jesus apparently did not share the hatred of His Jewish contemporaries and actually engaged the woman (who had dubious ethical standards) in a conversation starting at basic needs (water) and moving rapidly to the more urgent need of water quenching spiritual thirst. The biblical text seems to reflect a number of orthodox considerations about Samaritans. Jews would not speak to Samaritans or ask a single woman for water. In doing so, they would become unfit to enter the temple (John 4:9, 27). In fact, if possible, Jews would avoid crossing Samaritan territory (“heneeded to go through Samaria” [vs. 4, NKJV, italics supplied]). As the conversation moves forward, Jesus is not sidetracked by the woman’s attempt to “talk theology” when He gets uncomfortably close to the reality of her life (vss. 16–20). “‘A time is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem’” (vs. 21) is Jesus’ entry to a masterful introduction to the kingdom of God, involving Spirit-and-truth worship. Neither geography nor buildings determine a true relationship with the Creator but rather Spirit-guided worship based on truth—as revealed by Jesus. John’s repeated reference to “truth” points to God’s revelation that shows itself in action (John 1:17; 3:34; 8:32, 36). The significant prayer, already touched upon in the opening paragraphs of this study, includes also the promise of the “‘Spirit of truth’” leading all future disciples into “‘all truth’” (16:13).

Jesus’ reference to Spirit and truth at the center of His conversation with the Samaritan woman points beyond engagement to the foundation of true dialogue between (often competing) faiths. Ecumenical relations that do not consider the truth claim of Scripture (including “all the truth”) fall short of Jesus’ ideal. Jesus’ conversation at Jacob’s well underlines the importance of dialogue and engagement; however, Jesus did not model confrontation or debate. He reiterated revealed truth, pointing beyond theological nitpicking to missiological commitment, and ultimately calling for a decision. Amazingly, His venturing into Samaritan territory (and theology) bore rich fruits, for “many of the Samaritans from that town believed in him because of the woman’s testimony” (John 4:39).

Unity and the New Testament Church

The transition from Old Testament people to New Testament church was not an easy one. Yes, the timing was right and had been anticipated by the prophets (Gal. 4:4). Yes, Jesus’ death and resurrection had changed the playing field and had challenged key foundations of Israel. But there was no clear-cut division distinguishing easily between Old Testament and New Testament. The early followers of Jesus were steeped in God’s written revelation given by His prophets. While many read these texts in Greek (in the LXX), others still practiced their Hebrew and Aramaic in the synagogal worship service. But something different was about to take place, something that required no great theologians or scholars but the unifying power of the Spirit, working to constitute the new Israel.

Israel within the Old Testament world knew clear ethnic and national boundaries, and becoming part of Israel meant embracing a Jewish identity—including many ritual and ceremonial prescriptions, circumcision being one of them. By New Testament times, things had become more complex and the pull to integration with extremely divergent groups became a major challenge for the fledgling Christian Church. Even within Judaism itself were a number of intensely opposed factions (or sects), thus making a definition of orthodox Judaism during the time of Jesus more complex.

This may have been because of the fact that the Christian community rapidly moved from a group marked by ethnic links (i.e., one people, one land, under one God, which is ironically reflected in the Declaration of Independence of the U.S.A.) to a community of believers that transcended ethnic and social boundaries and thus was more vulnerable to external pressures from both the Jewish world in which it had its roots and the pagan communities surrounding it. As can be expected, this transition required careful maneuvering. Even the disciples, who had worked most closely with the Master, were not immune from an ethnocentric perspective when it came to salvation. It took God two extraordinary visions and miracles to overcome Peter’s (representing the early believers of Jewish descent) deep-seated distrust and theological concerns just to enter the house of a Gentile (and, far worse, a Roman army officer) and recognize in him a potential Christian brother (Acts 10).

Another case in point involves the early Christian Church’s dealings with the issue of circumcision and purity laws. As visible in the intense debate during the Jerusalem council (Acts 15), the church struggled with the issue of balancing the centrality of the Cross and of Jesus with the cultural and religious reality of most of its Jewish believers and the trajectory of the covenant people in the Old Testament. Paul summarized this dilemma in the following words: “Those who want to make a good impression outwardly are trying to compel you to be circumcised. The only reason they do this is to avoid being persecuted for the cross of Christ” (Gal. 6:12). As a matter of fact, Paul does not reject circumcision per se but echoed many Old Testament references that highlighted the importance of “heart” circumcision. “But he is a Jew,” wrote Paul, “who is one inwardly; and circumcision is that of the heart, in the Spirit, not in the letter; whose praise is not from men but from God” (Rom. 2:29, NKJV). Paul knew the Old Testament and understood that circumcision included something that went beyond the physical act of removing the foreskin of the male baby—true circumcision, repeat the biblical authors over and over again, involved the heart and mind (Deut. 10:16; 30:6; Jer. 4:3, 4; 6:10; Lev. 26:41, 42; Eze. 44:6–9).

On the other hand, there was the continuous threat of pagan practices (such as using meat sacrificed to idols [1 Cor. 10:28] or offering sacrifices to the Roman emperor), which would cause early Christians to compromise their faith and would neutralize their mission to tell of Jesus’ death, resurrection, and return.

The tension between the predominantly Jewish identity of many early followers of Jesus and the attraction to assimilate religious elements found in Greek and Roman culture is visible at many key places in the New Testament. “There is neither Greek nor Jew, circumcised nor uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave nor free, but Christ is all and in all” (Col. 3:11, NKJV), wrote Paul. The fact that Paul had to underline repeatedly the equality of Jew and Greek, or members of the covenant people (insiders) and heathens (outsiders), suggests this tension. “For there is no difference between Jew and Gentile—the same Lord is Lord of all and richly blesses all who call on him” (Rom. 10:12). Christians had to discover that they were something new—a community of faith that ignored regular cultural and ethnic markers (“neither Greek nor Jew”) and highlighted the inclusiveness of their community. In this sense, it had to straddle a thin line leading to a type of unity that was not based on ethnicity, locale, or culture—but that focused on Christ’s centrality and His mission to the world surrounding them.

Despite the storms of persecution, discrimination, and theological debate, the early post-Jesus church kept its unity and, driven by leaders such as Paul, focused on its calling to mission. While they stood apart on some issues of belief and worship practice (e.g., Christians would not, even under threat of death, offer a sacrifice to the emperor) the New Testament church engaged society and was not exclusive or monastic. They were truly “‘in the world, but not of the world’” (John 15:19, NKJV). Paul, who had been trained in rabbinical texts and reasoning but was also at home in Greek rhetoric and philosophy, made it clear that all he did was for one express purpose: “I have become all things to all men so that by all possible means I might save some” (1 Cor. 9:22), he writes. Mission drove him—as well as the larger Christian community as they awaited the coming of their Lord.

The Rise of Babylon: Babel Revisited

In 1910, at the World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh a resolution was passed to “plant in each non-Christian nation one undivided Church of Christ.”6 It would seem that missionary activities in the various non-Christian countries were being hindered by developing doctrinal tensions and “sheep stealing” instead of Christianizing the non-Christians. The idea of introducing an undivided Church of Christ to the world was laudable but immediately raised questions of what this undivided church of Christ would look like.

After an interruption by two world wars, the World Council of Churches was eventually established to promote unity among the different Protestant denominations. Seventh-day Adventists have never officially participated as members in the dialogue of the WCC. Our philosophy of history, our own past, present, and future is colored by the recognition of the great controversy that rages between God and Satan. Scripture traces some key points of this cosmic battle, including its beginning (Rev. 12:7–9), its course (Revelation 12), as well as the final outcome (19; 20). As a church, we consider ourselves not just another denomination with some peculiar doctrines adding to the patchwork of Protestantism. We recognize that we are part of a prophetic movement and, primed by Scripture, we pay attention to Satan’s strategies revealed in prophecy. This recognition is not cause for pride and arrogance. To the contrary, its commitment tosola Scriptura causes us to tremble at the threshold of the biblical text, to paraphrase the title used in a volume by James Crenshaw.7 Remnant theology within the context of a cosmic conflict requires humility and a Christ-centered approach that echoes Jesus’ own approach to truth and the Spirit-filled search for truth.

Revelation 13 introduces two symbolic beasts supporting each other. These two beasts refer to a religio-political power based on manmade traditions rather than God’s Word, with enough power to enforce their mandates worldwide. In other words, prophecy warned of a conglomerate of different religious groups that, under an extremely good guise, will be actively trying to derail God’s purposes. Numerous references in Revelation warn the readers not to “worship” the beast. In Revelation 16:12 to 16 (generally considered the sixth bowl), after the drying up of the Euphrates, John saw three unclean spirits—like frogs—come out of the mouth of the dragon, the mouth of the beast, and the mouth of the false prophet. The “three-ness” has been interpreted as a forgery of the true three-ness, the Trinity. This false trinity already made an incomplete appearance in Revelation 12 and 13 (dragon, two beasts) and has traditionally been interpreted by Adventist commentators as references to Rome (or Catholicism), fallen Protestantism, and spiritualism.

In the first century A.D., the Jewish nation rejected Jesus because it refused to believe the prophecies, which so clearly pointed to Him. They favored a different picture of the Messiah and were not ready to revise their one-sided reading of Scripture. Later, Judaism and Christianity shared many important truths, but Christianity could not sacrifice the Cross (i.e., salvation by faith in Jesus’ sacrifice) on the altar of peace and unity. First-century lessons of a movement that focused upon the proclamation (in deeds and words) of the kingdom of God are surely applicable to a church ministering in a postmodern context where differences are minimized and relevance and experience have become primary indicators of truth.

The prophetic interpretation informs any question of ecumenical relations now as it did for the early church. Although we may share many common essential truths with numerous Christian denominations or even some lifestyle components with other world religions, we cannot brush essential components of our biblical understanding under the rug considering prophetic end-time scenarios. Prophecy suggests that worship (including the day of worship) will be a crucial test of allegiance to God within the cataclysmic last events. On the other side, millions of Protestant Christians favor a futuristic or dispensational understanding of prophecy and have settled for the Rapture, while Seventh-day Adventists await the glorious return of our Savior who will “‘come back in the same way you have seen him go into heaven’” (Acts 1:11). Could it be that the crucial dividing line in the final events on planet earth will not put Christian versus non-Christian but rather my way/my truth/my interpretation versus His way/His truth/His interpretation—and thus be not that distinct from the theological battleground of the first coming of Jesus? Clearly, a biblical discussion of ecumenical relations cannot afford to ignore biblical prophecy.

Pentecost: The Reversal of Babel

From the above comments it may seem that any attempt at unity and ecumenical relations is inherently suspect. However, this is not the case. Jesus’ call to unity in John 17 is still much needed and relevant, but, as with salvation, it must be approached in God’s way, not our way.

Following the resurrection and later ascension of Jesus, the disciples, in obedience to the instruction of the Master, waited in Jerusalem. Acts 1:14 emphasizes the unity of the early Christian community and their prayerful attitude. Acts 2:1 locates the narrative in time (i.e., the “Day of Pentecost,” which is equivalent to the Israelite Feast of Weeks described in Leviticus 23:15–21) and again underscores the unity of the followers of Jesus.

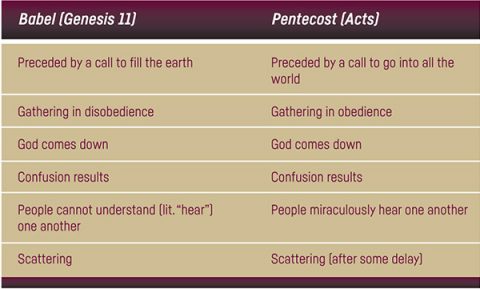

The fulfillment language of Acts 2:1 (and the numerous other fulfillment formulas included in the New Testament) remind the reader that the divine plan did not come to an abrupt end with the arrival of the Messiah. Rather, it represents a fulfillment of the promise given in Acts 1:4. Verse 2 describes a powerful sound “from heaven” that filled the house where the disciples were meeting. The Counselor promised by Jesus (John 14:16–18), the Holy Spirit, fills all present and they begin to speak in other “tongues” (Acts 2:4). This movement from heaven down to earth echoes the divine movement from heaven to earth in Genesis 11:5. And in line with Genesis where language became confused, Acts 2 involves speech that functions as some type of reversal from confusion (and lack of understanding) to understanding. Acts 2:6 and 7 note the surprise and shock of the multitude that gathered when hearing this strange sound, since all the visitors could hear the disciples speak in their own language. The links between Babel (Genesis 11) and Pentecost (Acts 2) can be summarized in the following table.8

However, Pentecost does not represent a return to linguistic uniformity. Language and culture still separate people. Rather, the unification is linked to a community—the budding New Testament church—and to a mission. This new ecumenical unity of Pentecost has a missiological perspective. The gift of tongues is given to empower a united community to reach the world. Furthermore, it takes down barriers that existed in the early Christian community—barriers between rich and poor, between Jews and non-Jews, between the stranger and the insider. Acts 2:4 reminds us that “all” were filled with the Holy Spirit—not just some carefully chosen leaders. Acts 10:44 to 46 revisit this important topic as the text describes the Holy Spirit’s falling upon the household of Cornelius—a foreigner and outsider and not a member of the covenant people. As these new Christians speak, the Jewish Christians accompanying Peter are amazed as they see the same phenomenon and understand the worship of their newly found brothers and sisters.

Mission needs to be the driving force for our desire for unity. The Seventh-day Adventist Church is not just a club of like-minded individuals sharing a common set of beliefs who meet once a week for fellowship and community. It must align itself with God’s great dream, the missio Dei, of saving a sin-sick world and proclaiming the kingdom of God that has already come and is about to break into our complacency.

Between Isolation and Assimilation

The Seventh-day Adventist Church in the 21st century is experiencing the same tension between exclusivism and inclusivism that was faced by God’s people in both the Old and New Testaments. Culturally diverse and often challenged by distinct theological perspectives, our unity is at stake and will have serious consequences for our mission as Seventh-day Adventists.

At the same time, postmodern culture, historical-critical hermeneutics and theology, and increasingly more fervent ecumenical movements in religious circles are challenging our unique identity as the remnant church. Jesus’ focus upon truth and the Spirit in His “ecumenical” conversations help us understand the importance of revealed truth and the blueprint for unity as presented in the Bible.

In both the Old and New Testaments, God’s people do not exist in splendid isolation, but always seem to be in dialogue with others. However, this dialogue does not happen on the terms of diverse or current political or cultural agendas, but rather on the terms of the revealed will of God. It is the existential interaction (both individually as well as in community) with this divine revelation that will provide a critical filter for all ecumenical activity.

As Seventh-day Adventist Christians, we do strive for and promote unity with others on common issues (e.g., religious freedom, specific relief projects, or carefully planned public engagement)—but are cautious of a theologically motivated union.

There are four elements that require attention when we want to think biblically about ecumenical relations:

1. It requires a crystal-clear idea of what our mission is.

2. It needs a clear understanding that the missio Dei is also our mission—and that this mission needs to be undertaken according to the principles of God’s kingdom (no coercion, no manipulation or compulsory activity, etc.).

3. It may also mean submitting our will and perspectives to be shaped and guided by God’s Spirit and plans. It does us well to remember that the first Christian mission drive was actually a response to persecution—something that does not look very promising or appealing in the rearview mirror.

4. And, finally, any ecumenical relations must be Scripture-based and driven by a vital relationship with Jesus.

When Peter and John were taken before the Sanhedrin in Acts 4, they were made a truly ecumenical offer: You can believe whatever you like, you can be another Jewish sect—but you cannot preach the name of Jesus anymore. For Peter and John, who knew Jesus personally, this was not an option. They were not trying to be different for the sake of being different, but they knew that wherever the present socio-political winds were blowing they had to “obey God rather than men!” Any ecumenical relations that are guided by our desire to be better known or more widely accepted or recognized and compromise on biblical truth are questionable.We cannot look for the lowest common denominator in our quest for unity.

Jesus commanded His disciples to stay and wait for the Comforter who would lead them into all truth (Acts 1:4, 5)—and empower them for mission. Our search for unity God’s way will lead to true John 17 unity and ultimately to the fulfillment of the great gospel commission: “‘This gospel of the kingdom will be preached in the whole world as a testimony to all nations, and then the end will come’” (Matt. 24:14).

Gerald A. Klingbeil, D.Litt., is an Associate Editor of the Adventist Review and Adventist World magazines and also holds an appointment as Research Professor of Old Testament and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan.

NOTES AND REFERENCES