Were Adventists to recover and expand the Adventist vision and apply it to the gospel, they would see and experience the true historical gospel as it is in Christ.

Fernando Canale

Part 2

Realizing that the danger of disunity challenges Adventism and its mission, the first article in this two-part series sought answers that might help the remnant church to achieve theological and spiritual unity and fulfill her God-given mission. It traced the main cause threatening theological and spiritual unity to the eclipse of Scripture in the mind and life of Adventist leaders and members. A brief survey of our history showed that Adventism originated as its formative pioneers discovered the biblical vision that led them to recognize and articulate the harmonious theological system of biblical truth. Yet, an increasing superficiality and disregard of Bible study has slowly led Adventism to lose its vision, thereby fragmenting its unity and weakening its mission. A return to Scripture may reverse this situation.

Living the Vision

What is spirituality? A cursory glance at newsstands or popular TV shows indicates that spirituality is a hot topic. There is a form of spirituality tailored to suit almost everyone—agnostic, atheist, or religious. Clearly, the definition of spirituality remains broad and ambiguous, meaning different things to different people. The dictionary states that spirituality is “the quality or state of being spiritual.” Spiritual, in turn, means something “relating to, consisting of, or affecting the spirit; incorporeal, relating to supernatural beings or phenomena.”1 With this definition in mind, we can identify the basic components necessary to experience spirituality as a phenomenon (events in our lives).

God and human beings are connected by a spiritual link (spirituality). These components may be represented by a figure resembling an American football goalpost. The sector above the horizontal post represents the supernatural side of reality we call heaven, and the lower section the natural side we call the world. The obvious distinction between the natural and supernatural sides of reality involved in spirituality is critical to understanding the role of the Adventist hermeneutical vision for spirituality and the church. But first, consider how the classical Christian vision (based on Greek philosophy and perpetuated by Christian tradition) operates in shaping Christian spirituality.

Classical Christian vision and spirituality. Early Christians habitually engaged in cultural accommodation. This is the process through which theologians and other church leaders adopted various pagan customs and rituals. But they also embraced a facile compatibility between Scripture and philosophy (the equivalent to our science), thereby compromising the authority and role of Scripture as sole source of divine revelation. At first, only a few philosophical ideas about the divine and human natures were adopted. Yet these accommodations, small though they may have seemed, played a decisive role in the interpretation of Scripture and construction of Christian theology.

a. Heaven and Earth. When Christ was born, the widely accepted cosmology was Neoplatonism. Just as present-day evolutionism expanded Charles Darwin’s seminal ideas, Neoplatonism worked out Plato’s cosmic views in early Christianity. Likewise, as evolutionary cosmology determines what we accept as real, so in the first centuries A.D., Neoplatonism determined what Christians accepted as real.

What we accept as real has a leading role in our theological thought. For instance, if evolutionary theory is accepted as true, it will dictate what can be accepted as real (factual). If you hold an evolutionary worldview, could you accept that the first three chapters of Genesis are speaking about reality, about what really took place in space and time? You will either say it is fictional, or perhaps use a more euphemistic term such as symbol or metaphor to describe the reality value of the Genesis 1 to 3 narrative. If you accept evolutionism as true, it dictates to you the parameters of what you may accept as real―which, in turn, must apply to the reading of the text to properly understand its meaning and value. In this way, evolutionism works as a vision that guides its adherents in their understanding of all reality. Similarly, in the early church, Neoplatonism was the accepted cosmology. When Christians began to apply it as a vision (to determine what was real or not in Scripture), the Roman Catholic Church began to emerge.

To return to the American football goalpost illustration, heaven and God would be above the horizontal bar, and the world below it. Platonic cosmology taught that while heaven was eternal, unchanging, and timeless, the world was transitory, changing, and temporal. Timeless reality was true reality (ultimate reality), and temporal reality was simply not real (illusory reality).

The reasoning behind this view is simple: What has no time does not change, and what does not change cannot pass away. Consequently, since God cannot change, He cannot be temporal because time is the measure of change. So, timeless eternity and immutability define God’s reality (Being). In short, Plato’s cosmological conception of reality requires that anything real be changeless and timeless.

From this we can detect that Plato does not use the word timeless in the commonly accepted sense of “permanence through time” (duration). For Plato, timelessness meant not having time, being void of time, not existing within the past-present-future flow of time. However, when, in common parlance, we say a piece of music or a painting is timeless, we are not saying that it exists outside of time, but that its beauty extends for many generations and its artistic splendor continues to be appreciated with the passing of time. What Plato taught, then, was foreign to common understanding even in the Greek culture of his day. For how does one begin to visualize things “timelessly real”? Do you know of anyone or thing that does not exist in time? Could you even imagine it? The best the philosophers could do is to say that only God can be timeless, and for that reason they placed Him under the rubric of mystery. This made little sense to common people, but they accepted the philosophers’ conclusions, assuming they must know what they were talking about. Furthermore, the early church fathers eagerly incorporated his and other philosophers’ views into church doctrine.

Thus, the early church discarded the biblical and popular concept of reality as temporal-historical to embrace the Platonic interpretation of reality as timeless. This seemingly small change placed the vision of Christian tradition on a vastly different foundation from that operating in Scripture. This fateful switch led to a progressive departure from Scripture and reinterpretation of its teachings. It wasn’t long before Aquinas’ observation was confirmed that “a small error at the outset can lead to great errors in the final conclusions.”2 Could timelessness be a “small error” leading to “great errors”? How would it work out? Unfortunately, it has already worked out. We are not facing a possibility but an actual fact.

To return to the figure of the goalpost, God is above the horizontal crosspiece. If we embrace the Platonic vision of reality as timeless, it will dictate what we can and cannot accept as real. For instance, when reading Exodus 25:8, where God declares: “Let them make me a sanctuary; that I may dwell among them” (KJV), we will be forced to interpret it symbolically or metaphorically, because the Platonic vision requires supernatural things to exist timelessly; that is, outside of the flow of space and time. What exists in time can only be natural, not supernatural. From Christian tradition’s perspective (vision), Exodus 25:8 describes God’s relation to believers symbolically rather than in actuality. Their guide, then, to understanding how God relates with humans is not Scripture but the Neoplatonic vision.

This is not an isolated case; it recurs every time Christian tradition interprets a Bible passage about God or heaven. When Christianity embraces the Platonic vision, it cannot but interpret the entire biblical revelation of God as symbolic.

Consider another example related to the sanctuary doctrine. The Adventist vision builds on the conviction that on October 23, 1844, Christ actually entered a real heavenly sanctuary to engage a new phase in the history of redemption. From the viewpoint of the Platonic vision, however, nothing could have happened in heaven because, according to it, “heaven” has neither space nor time. For this reason, Christian tradition sees the biblical doctrine of the sanctuary as childish fiction that confuses symbol with reality. This explains why, though Christians have long known the biblical teaching on the sanctuary, they have never embraced it as doctrine. Their Neoplatonic vision continues to prevent seeing, understanding, and following the real God of Scripture, the One who in reality acts within spatiotemporal history.

The Neoplatonic vision guides Roman Catholic and Protestant interpretations and practices of spirituality. By visualizing this connection, Adventists may better understand how a small error in vision at the beginning will unavoidably result in large errors in doctrine, practice, missionary planning, and expenditures at the end.

b. Spirituality. The term spirituality is commonly applied to the relation or contact that human beings can have with the “other side,” that is, with the supernatural. Since the first centuries A.D., Christians have adopted the Platonic worldview as their guiding vision. This vision sees God as consisting of a timeless, unchangeable Spirit in heaven and human beings of a body (matter) and soul (timeless substance) on earth. According to this vision, spirituality—as the encounter between humans and God—can occur only in the soul (spirit), never in the body (space and time). Spirituality, then, is considered an otherworldly encounter with God that we experience in our souls. What are the consequences of the Christian classical vision of spirituality for believers in the pew? Does this type of spirituality detract from biblical spirituality?

c. Spiritual disciplines. These are familiar surroundings—after all, aren’t we intentionally calling the church to engage in “spiritual disciplines” and “spiritual formation” as activities necessary to achieve the long-awaited revival and reformation? Many have felt free to embrace uncritically from Evangelical sources anything relating to spirituality and then insert it into congregational worship services or personal spiritual practices. There is confidence in doing so because it is assumed that, since Evangelicals accept Scripture, they must think and work from the same guiding vision that we embrace. Here is where Adventist believers are sadly and tragically mistaken. Evangelicals have always thought, done theology, and lived assuming the classical vision of Christian tradition. In recent times, however, by embracing the Emerging Church movement, even conservative Evangelical leaders are leaving not only Scripture but also the classical vision to embrace postmodernism. This affects not only their concept of spiritual disciplines but also their theological, ministerial, and missiological practices. Consider the way in which the classical vision shapes spiritual disciplines (spiritual formation).

In Christianity, “spiritual disciplines” is the general term given to any number of repetitive actions performed in order to facilitate the encounter or union with God. Adventists place the regular reading of Scripture and prayer at the center of the way in which they facilitate the encounter with God. We encourage the goal of spiritual disciplines as such. We know, however, that the classical vision places spirituality in the realm of the “spirit,” which supposedly exists outside of space and time. Consequently, those who embrace this vision experience spirituality in their souls. And here is where we encounter a problem. To experience Evangelical or Roman Catholic spirituality, you need to have a soul. Adventists, however, do not believe that human beings have a soul, but that each person is a soul. What is the difference?

Here we discover a component of the Adventist vision not yet addressed: the nature of humanity. Scripture does not support the Platonic view that humans are made of two substances, body (material, temporal, historical) and soul (immaterial, timeless, non-historical). According to Scripture, we exist as bodily (material, temporal-historical) souls. How does this doctrinal “pillar of Adventism” shape our understanding of spirituality in general and Bible reading (as spiritual discipline) in particular?

The classical vision demands that since God is spiritual, truth and experiences involving God should likewise be spiritual. That is correct, of course; the problem, however, lies not with what is seen in this statement but what is not seen. It is assumed that the “spirituality” of God and “truth” are both timeless. Yet, if all Scripture is historical and spatiotemporal, how does the classical vision arrive at the dimension of the spirit? The answer of both the classical and postmodern visions is the same: They arrive at the spirit through the allegorical (spiritual) interpretation of the biblical texts. The classical vision, then, can easily adjust to the historical criticism of modern and postmodern times by saying Scripture uses symbolic, metaphorical, mythical, or narrative language. Only by understanding that the text points beyond space and time to the spiritual realm where God is can one properly understand the ultimate spiritual function of the text and, therefore, the role of Bible reading as a spiritual discipline.

Thus, while Evangelical and Catholic spirituality “have room” for Bible reading, they believe Bible study should be avoided as an unnecessary distraction. After all, the meaning of the text is not really important because it speaks only about things relating to space and time (illusory, not real). Repetitive Bible reading of the same text, called lectio divinain classical Christian understanding, is necessary but only as a steppingstone to reach the next level: the spiritual timeless encounter with the other side (God). The historical truth spoken by God is not valued as actual content but only as the material sacramental vehicle used to communicate the spiritual timeless Word of God (presence of the eternal being of God Himself) in liturgy. So, according to the classical Christian vision, we should meditate/pray/repeat the words of Scripture to enter into the very presence of God. It is precisely this repetitive action and chanting that produces a kind of hypnotic effect leading to the euphoric state interpreted to be union with God. “Lectio divina has no goal other than that of being in the presence of God by praying the Scriptures.”3 Correspondingly, Bible study for the purpose of understanding God’s being, will, and teachings is considered irrelevant for spirituality and even counterproductive, as it engages the mind instead of quieting it.

According to the classical Christian vision, lectio divina (Bible reading) united with “contemplative” prayer are the vehicles to encounter the very being of God in the deep, timeless region of the soul. The goal of contemplative prayer, then, is to bring the actual Being of God Himself down to us, here and now. So, through a few repetitive practices, practitioners believe they can summon the actual God of the Universe in substance.

Working within the Neoplatonic vision, spirituality is defined as the personal encounter between the soul (timeless, spaceless, immaterial) and the being of God (timeless, spaceless, immaterial). Spiritual disciplines are basically repetitive rituals intended to suppress thought and foment feeling to experience the real presence of the being of God within the soul. Spiritual disciplines and worship, then, are two ways leading to the same end: the experience of a timeless God within the soul, which leads to the divinization of the soul. Once the soul is divinized, it has essentially become one with the Godhead, with no degree of difference or separation between the human soul and God. Thus, the goal of spiritual disciplines and worship is to bridge the separation between creature and Creator by completely eliminating space, time, and history from the Christian experience.

Seventh-day Adventist leaders would be wise to remember that Evangelical spiritual disciplines and spiritual formation assume the existence of the soul as a timeless spiritual substance and the seat of the self, reason, and spirituality. The first casualties in this concept of spirituality are Scripture and the incarnated and ascended Christ. In this model, spirituality does not center on the incarnated Christ and His revelation in Scripture. Of course, both are integrated, but merely as symbols, signs, and metaphors for ultimate-spiritual-timeless realities. Thus, in spiritual formation and worship, Evangelicals and Catholics use Scripture and Christ in a functional-sacramental way. This is a radical departure from the formative, spatiotemporal role of Christ and His Word presented in Scripture and embraced by the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Postmodern Christian vision and spirituality. The classical Christian vision is currently in the process of being revised. History shows how new scientific discoveries prompt the revision of previous visions. Thus, in earlier times, Neoplatonism upgraded Platonism, and in modern times, Neo-Darwinism has modified Darwinism. Similarly, in modern times (17th century to the first half of the 20th century) science prompted theologians to adapt the classical Christian vision. In postmodern times (second half of the 20th century to the present time), new scientific insights motivate postmodern theologians (Catholics, Protestants, and Evangelicals) to revise the classical and modern Christian visions.

Evolutionary theory is the new idea behind the modern and postmodern upgrades to the classical Christian vision. Like Plato’s cosmology, the consequences of evolution are broad and far-reaching. Challenging the supremacy of Platonism in the Western world, modernity unleashed a deep criticism and polishing of the classical vision that still goes on unabated. Recently, postmodernism has criticized and revised modernity. So, it should not be considered a complete rejection of classicism or modernity but rather as their full mature achievement. Postmodernity, then, is Ubermodernity.

In short, the postmodern Christian vision emerged from the modern evolutionary polishing of the classical Christian vision. The classical Christian vision was not rejected outright, but upgraded in at least two significant areas: (1) the “being” of God, and (2) the revelatory source. The “being” of God, which relates directly to the conception of heaven and earth, is now understood as panentheism. The revelatory source that relates directly to spirituality and the spiritual disciplines is now understood as a divine-human encounter.

a. Heaven and Earth. Pantheism and the slightly broader panentheism provide the best way to fit evolutionary cosmology with the classical Christian vision. Literally, panentheism means “all is in God. All that exists has its being within the being of God, but God transcends the universe itself. God is not identical with the universe (as in pantheism) because God is more than the universe, but the universe is coeternal with God.”4 Since, according to panentheism, there is no ontological separation between God and creatures, heaven and earth are words that describe different aspects of the same divine reality. Oneness is real, while multiplicity and divisions are illusory. Heaven is everywhere because God is all and therefore “everywhere.” Consequently, the basic biblical notion of divine dwelling is meaningless, even as analogy. Moreover, since God is all, He cannot indwell Himself. Neither can He “die for us” or “come again.” In short, there is no “God and us” as different entities that could relate to each other. Only God exists. And thereby all humans are gods.

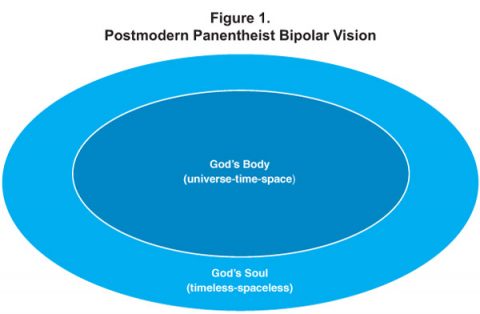

The classical (theist) and postmodern (panentheist) Christian visions assume the same distinction between a timeless heaven and a temporal earth, thereby revealing a basic harmony undergirding both visions. This is why the postmodern Christian vision embraces a “bipolar” view of God (see Figure 1). Panentheism applies the Platonic anthropological dichotomy to God so that, like humans, God also has a temporal body (the universe, represented in Figure 1 as a grayed smaller oval), and a timeless soul (heaven, represented by the white larger oval). The major difference, then, is the relocation of heaven within the universe (God’s soul) not beyond it. For this reason, heaven is not outside of us (transcendence) but within our souls (immanence). In embracing the time-timeless dualistic view of reality, however, a deep undergirding agreement is forged between the classical and postmodern Christian visions.

Christians adopting the panentheistic vision cannot accept the existence of heaven as separated (transcendent) from the universe. Thus, they reinterpret the concept of heaven by bringing it “down to earth.” Human beings experience heaven as the deep spiritual energy flowing from within their beings. Correspondingly, “the search for God” becomes “the search for the power of the inner life.” This brings us back to the issue of spirituality.

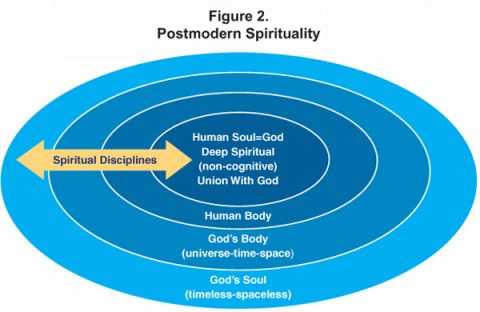

b. Spirituality: Union with God. Consider how today’s Christian postmodernists, Roman Catholics, and Emerging Church Protestant believers understand and practice spirituality. Figure 2 is a visual representation of the panentheistic worldview. There is no clear distinction between heaven and earth accepted in the classical Christian vision.

Spirituality continues to be a “contact with the other side.” The difference now is that because we are gods, the “other side” is no longer “out there in heaven” (transcendent) but “within us” (immanent). Yet, the “other side within us” is still timeless and the source of life power just as it is in classical Christianity, “out there in heaven.” It is no surprise, then, to find Christians advancing deep ecumenism not only between Christian denominations but also with other religions and even atheism.

Postmodern spirituality is the contact with the “other side” that is “within us.” When this contact is established (see arrow in Figure 2) spirituality is achieved through an encounter with the deep, timeless, life-giving dimension of God (the one reality).

Because the theistic-classical and panentheistic-postmodern visions embrace the same bipolar interpretation of reality (being), they will offer a similar understanding and experience of spirituality. In fact, both seek to experience union with God in the soul as a real but non-cognitive experience that goes beyond thoughts and words.

This general conviction is reinforced by modern science, which teaches that humans can know only spatiotemporal realities. Accepting this as true, Schleiermacher concluded that if we think of God as timeless (according to the classical conception of God’s reality) and of human thinking as spatiotemporal (according to science), God cannot be knowable. Therefore, he thought, if humans cannot know God by spatiotemporal thinking, they could imagine Him with their minds and feel Him with their timeless souls. Consequently, Schleiermacher believed that Christianity was not based on the knowledge of God (revelation/doctrine) but on the experience of God (encounter/spirituality).

The postmodern vision, then, arrives at this question: How do humans experience the timeless, spaceless, unknowable Spirit of God? Basically, the non-cognitive encounter between a timeless God and temporal human beings can occur in one of two directions: from God to humans (predestination-justification by faith) or from humans to God (spirituality). Not surprisingly, the legal aspect of the interpretation of justification by faith (forensic justification) advanced by the Protestant Reformation has not satisfied the spiritual needs of human beings. To fill this spiritual vacuum, Protestant and Evangelical believers are now seeking spiritual experiences that borrow from classical Roman Catholic and Eastern meditation techniques.

The postmodern vision believes God’s thinking is done in His temporal role by human beings who do God’s thinking. Human thinking is therefore divine thinking. Yet, in His timeless role, God is also an impersonal force that empowers humans from within. Humans are gods doing the divine thinking but also have within themselves the timeless non-cognitive impersonal divine presence providing “live energy” to be fully gods. In this vision, then, union with God takes place as a spiritual experience between humans and their inner divine “self” or “energy.” In essence, postmodern Christian, classical (Roman Catholic, Protestant), Emerging Church, and New Age spiritualities are the same. For them, union with God takes place beyond human consciousness—beyond space and time.

Apart from the conferral of divine spiritual energy (power), what are the consequences of this union for the Christian and the church? The union with God (encounter) facilitated by spiritual disciplines or worship produces a deep powerful “stirring” in the innermost depths of the soul. This stirring, however, takes place in what is considered to be the timeless, spaceless, unconscious level of the soul; that is, in the supposed non-historical level of reality.

Nevertheless, postmodernism recognizes that the soul still finds itself within the spatiotemporal level of the body. Although the soul is in the body, the encounter with the presence of God in the soul cannot connect with human temporal thinking. It does, however, indirectly reach the feelings. Even though one cannot communicate feelings directly to other human beings (because by nature they are personal and incommunicable), they can be shared indirectly through language by associating them with images present in the mind at the time of the encounter that generated them. So postmodernism says that words are chosen that are associated with those images to speak of the feelings awakened by the encounter. This movement is believed to take place in the body (the brain), where feelings are produced, experienced, and connected with thoughts and words in the imagination (consciousness). By words and acts, humans are considered to express the thoughts and feelings awakened by the timeless union with God in the soul. These expressions originated in what postmodernists consider to be the myths of Scripture, which include Christ’s divine nature, doctrines, and human works. All of these are considered to be expressions of worship (praise), voicing the subjective feelings of timeless encounters.

c. Spiritual disciplines. According to the postmodern Christian vision, spiritual disciplines and postmodern worship styles are necessary to facilitate union with God that brings eternal life (experience of salvation). However, by making human beings gods (having God within) the panentheistic worldview denies any superior status to Jesus Christ. Christ is just another human being. True, Christ is divine, but so are you and I. Consequently, postmodern Christianity sees Jesus as an important “spiritual leader,” just like Buddha, Confucius, Muhammad, or Moses were in their times. They distinguished themselves because their strong spirituality and personal skills allowed them to persuasively communicate their feelings about the encounter with God. Similarly, postmodern Christianity and the some in the Emerging Church no longer consider the Bible to be a divine book. For them, the Bible is a book of religious myths, written by human beings. In them are allegories, symbols, and myths attempting to communicate the spiritual, non-cognitive encounter of their writers.

According to the postmodern Christian vision, spirituality and worship are two words describing the same liturgical phenomenon, namely, the rituals necessary to get in touch with the other side. Because God is literally in all and the difference between sacred and profane has disappeared, worship rituals are all-inclusive. To fit personal and cultural preferences, any ritual, ancient or modern, is accepted and included. Yet, as noted earlier, the belief that the other side is timeless establishes a decisive continuity between the classical and postmodern Christian visions. This continuity shows up in the postmodern embrace of Roman Catholic (ancient) sacramental worship and spirituality. Not surprisingly, many postmodern Evangelical leaders are making the Eucharistic celebration central to their worship. This takes place because their vision also requires a material-spiritual (temporal-timeless) bridge to reach the deeper spiritual (timeless) side of divine reality. They find this bridge in the classical sacramental liturgical structure of worship on which the Roman Catholic Church stands. Thus the sacraments, not Christ, are the necessary bridge to reach eternal life. Rituals, understood sacramentally, are the material means to reach the power of timeless divine grace and even union with God, according to both the classical and the postmodern Christian visions. This basic ontological agreement calls for similar spiritual disciplines and spiritual life, and facilitates deep global ecumenism.

The classical vision under the authority of the Roman Catholic Church reduced the number of sacraments to seven. The postmodern vision, however, opens the door for any number of spatiotemporal (material) realities to become sacraments through which the other side can be reached. Furthermore, in and after Vatican II, Roman Catholicism began to embrace salient tenets of the postmodern vision, and is even becoming “Evangelical” in pastoral outreach and methodology. Enticed by the success of Pentecostal-style worship in reaching secular culture, popular music has become the de facto “ecumenical sacrament” par excellence for Roman Catholics, Protestants, and Evangelicals alike. According to this vision, popular music is the instrument (sacrament) to bring all cultures into a euphoric experience of God’s presence.

Moreover, according to the postmodern vision, spiritual disciplines also play an important role, helping seekers and believers to obtain a spiritual experience with the other side (spiritual energy). Ancient, Medieval, Eastern, and New Age spiritual disciplines become instruments to leave behind the realm of history (everyday experiences, words, images, thoughts, concepts, and consciousness) and enter the realm of “mystery” (the non-cognitive, timeless, spaceless, immaterial, non-historical Spiritual Energy that is called “God”).

Many Bible-believing Christians are enticed to embrace spiritual disciplines because they include and encourage Bible readings and prayer. However, as in the classical vision, the use of Scripture is more chant-like than thoughtful study. Similarly, prayers are not communication of thoughts and feelings to God as in a dialogue with a friend, but “contemplative” mind-emptying techniques to enter the “silence,” such as visualization, breathing, and chanting mantras. Furthermore, Bible readings and prayer are only preliminary steps leading the seeker to the final destination, the realm of mystery that lies beyond words, thoughts, and consciousness. The goal is not to teach humans how to dialogue with and depend on the incarnated, ascended, ministering and soon-to-return Christ. In fact, an encounter with Christ is completely absent from the spiritual disciplines of classical and postmodern Christian visions. Instead, their ultimate goal is to achieve ecstatic timeless encounters with the vague and mysterious other side and unleash the power of the god within.

By applying the classical and postmodern Christian visions to spirituality, a difference is noted in the way they understand the foundation from which they operate. The source of the classical Christian vision is the cognitive revelation of God in nature (which includes reason, tradition, and spiritual experiences) and Scripture; they are the ground on which it builds doctrines and practices. Conversely, the source or ground of the postmodern Christian vision is the non-cognitive union with God. In short, according to the classical Christian vision, knowledge and doctrine precede and ground experience; according to the postmodern Christian vision, experience and feeling precede and ground doctrine, including the Bible. In short, to experience God and find eternal life, there is no longer a need to bother studying the Bible (classical vision). Instead, to achieve union with God and tap into the source of eternal life, one need only to practice spiritual disciplines (postmodern vision). The postmodern Christian vision, then, totally neutralizes Scripture.

Adventist vision and spirituality. Obviously, Adventism cannot follow either of these other visions without destroying its very essence as Christ’s remnant church founded on the sola scriptura principle. As noted earlier, the Adventist vision has already modified and replaced both the source and the vision of classical and postmodern forms of Christianity. By recognizing from Scripture the actual historical presence of Christ in the heavenly sanctuary and His continuous mediatorial work for our salvation, Adventist pioneers completed the paradigm shift begun by the Protestant Reformation. If the Seventh-day Adventist Church were to abandon her own original conception of whence she came (Scripture) and her formative sanctuary vision, she would necessarily divide, stop growing, or even cease to exist. The stakes before the church cannot be higher.

The sola scriptura principle is the source from which Adventism was birthed and the foundation on which it builds. Additionally, formative Adventist thinkers discovered the integral role of the sanctuary as the macro-hermeneutical interpretive vision presented by Scripture. But some additional details are needed about its contents and function.

As the other visions, the Adventist vision includes a worldview―that is, a broad concept of the nature of reality as a whole. Such an all-inclusive view assumes and builds on an interpretation of the nature of reality (ontology), both natural (created) and supernatural (created and uncreated). An “unintended” consequence of the sanctuary was the temporal-historical view of the nature of reality as a whole. Any Bible reader is familiar with this fact. God interacts with His creation exclusively through time and space. That should have been inconsequential were it not for the fact that Christian tradition as a whole (classical and postmodern visions) have chosen to follow the timelessness of Eastern and Greek philosophies. This historical fact places the Adventist vision on a collision course with all other Christian and religious traditions of the world.

a. Heaven and earth. Since their beginning, Adventists have understood Christianity from the perspective of the Great Controversy between Christ and Satan. By thinking that Christ’s actions in the Great Controversy are real, historical events and not fictional myths, Adventists have always implicitly assumed that God is in some way temporal. Of course, in doing so, they are not implying that God is limited in any way to human temporal and spatial finitude. Yet they clearly see God Himself acting in a temporal sequence of past-present-future real actions including creation, Christ’s incarnation and sacrifice on the cross, His ministry in the heavenly sanctuary, and His second coming. Moreover, they also find in Scripture the teaching that God has no beginning (John 1:1) or end (Heb. 7:3; Ps. 102:27, Luke 1:33) and experiences time in ways completely different from His creation (2 Peter 3:8). How, then, does the basic biblical conviction that God lives and acts in a temporal sequence shape the Adventist vision and its biblical worldview of heaven and earth?

Because (following Scripture) the Adventist vision conceives of reality as temporal while Christian visions (following Greek and Eastern philosophies) conceive of reality as timeless, they are not complementary but mutually exclusive. Thus, a choice must be made between them. Christianity must choose between the sola scriptura principle and tradition. This is the parting of the ways, the “continental divide” in church history.

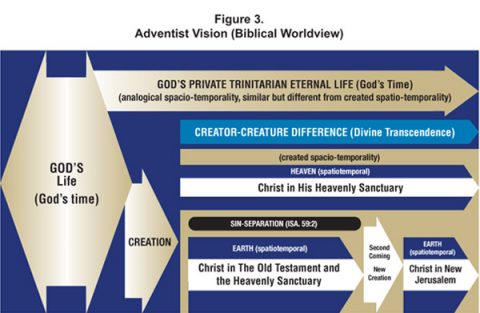

Figure 3 outlines the overarching structure of the Adventist vision. Because reality is temporal and not timeless, the graphic must be read horizontally, from left (past) to right (future). Beginning at the far left, we find a large arrow, indicating the infinite temporal life of the three divine Persons (Trinity), which have always existed and will continue to exist without end, independent from the creation (as illustrated by the top arrow that indicates the continuation of God’s eternal temporal life).

Immediately after the first left arrow is another arrow issuing from the eternal life of the Trinity, indicating the creation of the spatiotemporal universe. Then to its right is a vertical black line showing the temporal starting point of creation and its limited spatiotemporal nature. From the top end of the vertical black line flows a horizontal black line pointing out the continuous existence of the temporal universe throughout created time. Above this horizontal black line is a gray arrow, indicating the Creator-creature difference (transcendence) that has existed since creation between God and the universe. Thus, the difference between the Creator and creature does not stand on the timelessness of God, but on the infinity of His temporal, creative, omnipotent being. Because God’s existence is infinitely and analogically temporal, however, He can interact directly with created history (historically) at any time and in various and diverse ways within the limited sphere of created history. In fact, Scripture depicts Christ as playing the central role in creation history, in its origination, sustenance, coherence, and direction.

The top gray horizontal arrow immediately below the horizontal black line indicates heaven as a geographical region in the universe. This is where Christ now resides and rules over the angels in His heavenly sanctuary (white arrow within gray top arrow). Underneath, a horizontal black bar indicates sin as the dividing line between Christ/heaven, and the fallen planet Earth. Just below, there is another gray horizontal arrow indicating the existence and history of our planet. And inside it is a white horizontal arrow indicating Christ’s central presence and work of redemption. This presence was accomplished through several means, notably the Old Testament sanctuary, His bodily sanctuary (incarnation), His work from the heavenly sanctuary and through the earthly, indwelling presence of the Holy Spirit. These two arrows represent the entire range of Earth’s history from past creation to future divine events, the second coming of Christ, the eradication of sin, and the restoration of the original perfect order of creation through God’s promised new creation.

b. Spirituality. Spirituality is the close personal relation between God and human beings, theologically known as “union with God.” Different traditions using different visions of heaven and Earth interpret and practice spiritual disciplines and union with God differently. At this point, we need to review the way in which the Adventist vision of heaven and earth shapes the interpretation and practice of spirituality and union with God.

Since spirituality is the personal relation between God and human beings (union with God), it must take place in a realm in which both can meet. When the classical and postmodern visions interpret the spirit of God (heaven) and the spirit of human beings (Earth) timelessly and spacelessly, union with God must take place outside of history. In this scenario, spirituality exists timelessly and spacelessly outside the causal flow of history. When the Adventist vision interprets God (heaven) and human beings (earth) temporally and spatially, union with God and spirituality must exist temporally and spatially within the causal flow of history. Mutually exclusive interpretations of vision unavoidably lead to mutually exclusive interpretations of spirituality (union with God) and spiritual disciplines.

But how can we, finite creatures, find and relate with the infinite God within the flow and limitations of created history? To relate to God, we need to be in His presence. Historical spirituality, then, requires the historical presence of God within created human history. But how can the infinite Creator God dwell with finite creatures? Both classical and postmodern visions believe a timeless God cannot dwell with temporal beings. For these, timelessness and temporality do not mix. Alternatively, the Adventist vision embraces an infinitely and analogically temporal interpretation that easily allows God to accommodate His infinite being to the finiteness of creation. More can accommodate to less, but not vice versa. In other words, according to the Adventist vision, God, being infinitely more than His creatures, chooses to limit and accommodate Himself to His creatures in order to relate with them. This God has done in Christ ever since the creation of the universe.

Yet, even while existing in the very presence of Christ (union with God), Lucifer decided to rebel against Christ permanently and extended his domain to planet Earth. That’s when things got complicated. Sin as rebellion made union between the holy presence of Christ and human beings on planet Earth impossible. A line of demarcation had to be drawn.

After Adam’s sin introduced the reign of Satan on earth, Christ became “invisible”―not because He could not be seen, but because the holiness of His presence would consume sinners. It was not God’s will, but our sin that became the barrier (Isa. 59:2) preventing access to Christ’s visible presence directly in everyday life. In other words, what separates us from the visible presence of God is not His timeless nature (classical metaphysics) but our sins (Gen. 3:8). For this reason, to achieve union with God, human beings do not need to overcome their limited created natures (tap into their “timeless souls”) as both the classical and postmodern visions teach. Instead, they need to overcome their sinful nature as the Scriptures teach (Isa. 59:2).

To overcome our sinful nature, however, we must see Christ and commune with Him. Even after sin, access to the visible historical presence of Christ remained the only way to spirituality and union with God. To make spirituality possible, Christ had to bridge the sin barrier, which He did immediately after Adam and Eve sinned (Gen. 3:9). From then onward, Christ made Himself present to a few chosen representatives (patriarchs, prophets, and Moses). To them He revealed Himself through words (audible presence) and theophanies (visible presence). Finally, Christ became visibly present by becoming a human being (John 1:14) in this sinful world (Rom. 8:3). He gave Himself to the human race, forever to retain His human—as well as His divine—nature.

Thus, the historical-visible presence of Christ has been granted to certain human beings ever since the Garden of Eden and after Christ’s incarnation through the visible face of Jesus Christ (2 Cor. 4:6). After His physical ascension, we must follow Christ as He intercedes for us in the heavenly sanctuary to “see” (understand) Him, until He returns and we behold Him face to face. The centrality of Christ, then, places Adventist spirituality on a different foundation—and at odds—with classical and postmodern Christian spiritualties. Adventist spirituality is union with the historical Christ and thereby decidedly departs from the widely accepted notion that spirituality is union with God as timeless non-historical Spirit.

c. Spiritual disciplines. Spiritual disciplines are repetitive actions performed to achieve union with God. The question now is how does one approach the presence of Christ and experience union with Him? These issues involve human nature and experience. Grounded in a spatiotemporal vision of God (heaven) and human beings (earth) Adventist spirituality seeks to experience the incarnated Christ historically. To achieve union with the divine, then, is to know (1) where to find Christ today, (2) how to reach Him, and (3) what to do to achieve union with Him.

(1) Where is Christ found today?

Invariably, a large portion of Christians will answer this question by stating that Christ is in heaven (Acts 1:9–11). Because their respective visions interpret the nature of God and heaven differently, however, they have slightly different views on this point. On the one hand, classical (conservative) Catholics and Protestants believe Christ is in heaven with a “spiritualized” (timeless) soul-like body. On the other hand, postmodern (liberal) Christians believe Christ is in another more spiritually (timeless) evolved dimension of the universe, having a spiritualized soul-like “body.” Both views hold that in heaven, Christ no longer has a material spatiotemporal body. For all practical purposes, then, they believe that after His ascension, Christ assumed the same divine existence He had “before” the incarnation. Radically disagreeing with both views, the Adventist vision adopts the biblical view that Christ is in heaven with the same spatial limitations imposed by His human body (1 John 4:2). In other words, after the ascension, Christ continued to have the same human body He had during the incarnation. The spatial limitations of Christ’s body prompted Him and the Father to send the Holy Spirit as Christ’s representative (John 14:16, 17) to “dwell” with humans. By determining the reality (ontology) of Christ, visions predetermine the nature of spirituality and spiritual disciplines required to enter into union with God.

Though the Adventist vision places a spatial distance between Christ and humanity, the classical and postmodern visions place an ontological distance. Spirituality and spiritual disciplines must “bridge” the distance. Christian theologians have always correctly spoken of Christ as “the highest revelation” of God’s being. By denying that Christ has a material historical body in heaven, however, they imply that such revelation is no longer necessary. They claim that since the incarnation and ascension of Jesus, there is a new and better spiritual way to reach the very presence and being of God beyond the incarnated historical Christ. This new way is through the sacraments and spiritual disciplines. The inconsistency of this conviction extends to many foundational issues in the classical and postmodern systems of Catholic and Protestant theologies. These Christians unfortunately forget that while Christ was ascending to heaven, angels reminded His disciples of the promise that “‘this Jesus, who was taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven’” (Acts 1:11, ESV).5

Where is Christ today? He is in heaven and soon will return (John 14:3). This does not mean that humanity must wait until Christ’s second coming to experience union with Him. Because Christ was, and through all eternity will be, the highest and deepest revelation of God, believers must relate to Him by remembering Him as they meditate on all His words and actions. Christ instituted holy communion so that, until He comes back, we may relate to Him by bringing back to mind what He has done, taught, and promised throughout the history of salvation, especially during His earthly ministry (1 Cor. 11:25, 26). Moreover, through the invisible presence of the Holy Spirit as Christ’s representative by our side, we have all the advantages the disciples had when Christ lived with them. Obviously, we long to see Him face to face. At His second coming, we will find eternal rest in Christ and His kingdom.

This is the ground of Christian spirituality and the way to experience union with Christ. According to the Adventist vision, then, Christian spirituality is centered in the incarnated, ascended, ministering, and soon-to-return universal King: Jesus Christ. In short, according to Christ, Christians must keep Him in their minds and reflect Him in their lives (spirits). This indwelling of Christ is achieved through His Holy Spirit sent precisely to help us remember, understand, and practice Christ’s teachings, works, and promises (John 14:26) so that they may change us into His likeness.

(2) How do we reach Him?

But how can we, who never knew Christ personally, remember Him? We must do as the disciples and the Ephesians did, by learning about Christ (Eph. 4:20, 21). We do this by taking in the bread of life―that is, the words of life He spoke (John 6:35, 63). Those who partake of Christ must then teach about Him to other Christians who still need to learn of Him. Teaching, then, is the “ministry” of pastors, and study is the “spiritual discipline” of believers. Paul explained that Christians must be “taught in him, as the truth is in Jesus” (Eph. 4:21).

We need to learn of Christ because without faith, we cannot draw near or please God (Heb. 11:6). We need faith that “comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ” (Rom. 10:17). So, our salvation, faith, and spirituality require Bible study leading to understanding of God, not just from our leaders, but from everyone. Study is necessary because we must feed on Christ Himself, the Bread of Life that came from heaven, to nourish and enliven us through His words (John 6: 57, 63).

Moreover, according to the Adventist vision, union with Christ does not mean participation in the eternal divine life of the Trinitarian being of God, but participation in Christ’s history, character, and kingdom. More specifically, the union with God is not a union or identity of beings in which God’s divine entity is actually within the human entity, or vice versa. On the contrary, in the union with God, both God and humans remain separate entities, as in the case of oneness between husband and wife (Matt. 19:5). The union is real but only relationally, not ontologically. In the union with Christ, He remains outside of us in the heavenly sanctuary (and the Father and Holy Spirit as well), and we remain outside of Him. The union is a real spiritual identity between the mind-character-feelings-will-purposes-mission (spirit) of God and the mind-character-feelings-will-purposes-mission (spirit) of human beings. When we experience this identity, we partake in the divine nature (2 Peter 1:4). By faith in Christ’s person and work and His ongoing ministry in the heavenly sanctuary, then, we are adopted (saved) into the family of God (Eph. 2:19; 1 Tim. 3:15) rather than divinized by partaking in the inner life of the transcendent Trinitarian Being.

(3) What do we do to achieve union with Christ?

According to the Adventist vision, to experience God spiritually, we do not need to leave the spatiotemporal realm of everyday history because God’s analogical infinite temporality allows Him to exist as God within the limitations of created time. He accomplishes this in Christ. To achieve Christian spirituality, then, we must relate to the incarnated Christ, whose words and acts we find in Scripture. We do not need to abandon our consciousness or “enter the silence.” All to the contrary, we must use our minds because Christ became flesh with the precise intent of interacting with us within our limited spatiotemporality.

Addressing this experience enters the realm of spiritual disciplines. Eternal life is to know the Father and Christ (John 17:3). Since we know both the Father and the Son through Christ (14:6–9), how do we know a historical person such as Jesus was? In the way we know persons who live around us; merely looking at their physical appearance is not enough to know them. We need to listen carefully what they say and contemplate attentively what they do. Yet, to know persons intimately, more is needed. We need to know their origin, life, and personal experiences (histories). To know Jesus is more than imagining His physical form or gaining some isolated biographical information. We need to know His history.

Yet, because according to the Adventist vision the historical Person of Christ is presently in the heavenly sanctuary, how do we relate to a person so far away? We connect and relate to Christ through study and prayer. These are the basic Christian spiritual disciplines around which all others revolve. For this reason, Christ exhorted us to Bible study and prayer. Although all Christians embrace Bible reading and prayer, these “disciplines” play quite a different role in the Adventist vision.

Scripture provides not icons, symbols, or myths, as in the classical and postmodern spiritual disciplines. This is why to know Christ, we need to study the Bible. To behold Christ, we need individually to dig deep (study, research, meditate) in Scripture. A simple reading from cover to cover will not suffice. For the sake of eternal salvation, we must study the Scriptures as if mining for gold―deeply and passionately. While reading is to look and understand the meaning of words, to study is to learn, educate oneself through research, examination, observation, and meditation. Adventist spirituality requires deep personal and congregational Bible study―from the General Conference president to the most recent brother or sister baptized into the church. Studying Scripture is to hear the words of God, to discover Christ’s history, words, and acts and thereby come to encounter Him. This side of eternity, there is no other way. We study Scripture and its doctrines, then, not merely to gain head knowledge, but also to know Christ, to relate to Him, and to become united with Him (heart knowledge).

Studying the Bible with the purpose of entering into union with God revolves around the history of Christ in the Old and New Testaments. In Scripture we hear His words and contemplate His actions. We look to the past, beholding Christ, who created heavens and earth, gave the Law, dwelt with and guided Israel, and dwelt personally with the disciples. We look at the present, beholding Him in the heavenly sanctuary continuously working out our salvation (Heb. 7:25). We look at the future and find hope in beholding the promise of His soon return. When we worship, pray, and seek union with God, we direct our minds to the heavenly sanctuary where Christ now is, and in everyday spirituality our hearts anticipate His soon coming with sublime expectation. As we contemplate in our hearts the past, present, and future events of Christ’s life, our daily spiritual life grows.

Yet, knowing Christ’s history is not enough to enter into union with Him. The Bible is not Christ. Christ is not in the Bible. To achieve union with Christ, we must relate to Christ’s past through His present existence in heaven and future promises. Christ is as real today as He was in the past and will be in the future. “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever” (Heb. 13:8). We do not relate to God and experience union with Him through ecstatic feelings but through faith in the One who exists in heaven. Faith is the substance of events we do not see (past and present works of Christ) and events that are not yet (Christ’s second coming) (Heb. 11:1). Faith is trusting with full conviction and certainty in the historical acts and promises of Christ. So it is that we achieve daily union with God by faithful surrender to the historical Christ who speaks to us through the words of Scripture (past) and applies them to our life (present) through His continual work in the heavenly sanctuary and the ministry of His Spirit on earth.

According to the Adventist vision, spirituality and union with God take place when by faith we behold in Scripture the face of Jesus Christ (incarnated Christ) and are transformed by Him into His likeness through the teaching ministry of the Holy Spirit (2 Cor. 3:18; 4:6). This is the nucleus of Christian spirituality.

Union with God, however, is a two-way street; it is a dialogue, not a monologue. As God speaks with us through His Word, we must also talk to God in personal, private prayer. As God already has opened His heart, feelings, and actions to us candidly in Scripture, He expects that we will reciprocate in prayer. Scripture invites us to talk to God (pray), confessing our sins and opening the secret recesses of our hearts to Him―imploring forgiveness and asking direction and help to face the challenges of daily life. For this reason, we must not pray “contemplatively” to leave all actions and thoughts behind or hear God’s audible voice inside our heads or in the silence of an ecstatic (mystical) encounter. In Scripture, God prescribes prayer not as a form of contemplation designed to help us exit our thoughts to achieve an ecstatic (mystical) experience of the timeless mystery of God (classical and postmodern spiritual disciplines). Instead, God instituted prayer as the divine technology that allows us to talk to Christ directly as to a friend. When we pray, we must actively communicate our thoughts, feelings, and desires to Christ in the context of our daily experiences. Union with Christ, then, requires an ongoing dialogue between Christ and us (Bible study) and us and Christ (prayer) through faith (the disciple’s total surrender to Him). If we abide in this dialogue (John 8:31; 1 Thess. 5:17), we will experience union with Christ.

In studying Scripture we also discover the Holy Spirit is actively involved in our dialogue-relation with Christ. As an ever-present, providential divine Teacher sent by Christ and the Father to continue Christ’s ministry on earth, the Holy Spirit helps us to understand God’s Word and apply it to our lives. If we ask in faith and surrender our will completely to His revealed will, Christ promises He will give us whatever we ask in His name (John 14:13). If we by faith follow His teachings, believe His promises, and ask in His name according to His will, He is faithful in everyday life to respond to our prayers through the presence, providential guidance, and care of His representative, the Holy Spirit, who is also involved in presenting and answering our prayers according to God’s mercy and providence.

While Bible study, prayer, and the presence and work of the Holy Spirit are essential to achieve spirituality, union with God involves yet more: commitment and service to Christ and to the mission of His church. Praying students of Scripture must become disciples (followers). To become disciples, we must connect with Christ by faith (total submission of the will). Surrender of the will to the incarnated, resurrected, ascended, ministering (in the heavenly sanctuary), and soon-returning Christ involves not only careful and continuous learning. Continuous learning comes through disciplined Bible study, but also when one has an open heart willing to live according to all its words, teachings, commands, and promises (Rom. 2:13). Only when we connect with Christ in this way will we become truly His disciples, who achieve union with Him. Since Christ is God, spiritual union with Christ is union with God. Clearly, while classical and postmodern spiritualities are God-centered, Adventist spirituality is Christ-centered. According to the Adventist sanctuary vision, then, Christ is all for the disciple.

The spiritual disciplines of Bible study, prayer, and mission must be exercised continuously to enter by faith into union with God. As we are exhorted to pray without ceasing (1 Thess. 5:17), so we must walk with God continuously, as did Enoch, by keeping His words and actions fresh in our minds and engaging in the mission of the church. We achieve union with God, then, through the dynamic, continuous, two-way relationship of full openness to the past, present, and future actions of Christ our Savior, High Priest, Lord, and King. Moreover, union with God means to follow Christ wherever Christ leads and to do whatever He commands. We are united with Christ when our thoughts, character, desires, feelings, will, purposes, actions, and mission are the same as His.

From the beginning, Adventist spirituality existed and was empowered and motivated by the expectation of the blessed hope of Christ’s soon return, the renewal of all things, and the installation of His eternal kingdom on earth. Our greatest hope is to see the face of the One who died for and stayed by our side all the way. What a joy it will be to talk with Him and to know Him more fully! The Second Coming will complete the spiritual experience and union with God, which we may enjoy now only partially and in expectation.

The Vision-Spirituality-Church-Mission Connection

This survey of the classical, postmodern, and Adventist interpretations of spirituality and spiritual disciplines shows diametrically opposed approaches to Christianity. Not surprisingly, the kind of church and mission that necessarily flow from them is vastly different as well. This opposition is caused by the undergirding vision guiding each approach to Christianity. While we may ignore, we cannot deny the causal connection that exists among vision, spirituality, church, and mission.

All Christian churches accept the indisputable fact that the church is a spiritual community around Christ. Just as spirituality is union with God (Christ) on a personal level, the church is union with God (Christ) on a social level. As such, spirituality and ecclesiology belong together. Yet, because Christians interpret Christ and spirituality using both biblical and non-biblical visions, they understand Christ in diverse ways. This takes place because a causal connection exists between vision and spirituality. The vision contains the ideas (cause) necessary to understand spirituality (effect). This means that different visions will not only generate different understandings of spirituality but consequently also different understandings of the church and her mission. Consequently, when we engage in mission we assume (consciously or not) an understanding of the church, spirituality, and vision. When Adventists say they are the remnant church, much more is involved than the biblical marks of the eschatological remnant.

The connection with spirituality and vision explains why the mission of the church depends directly on the spiritual connection of each member with Christ and the consequent unity of all believers. “The unity, the harmony, that should exist among the disciples of Christ is described in these words: ‘That they may be one, as we are.’ But how many there are who draw off and seem to think that they have learned all they need to learn. . . . Those who choose to stand on the outskirts of the camp cannot know what is going on in the inner circle. They must come right into the inner courts, for as a people we must be united in faith and purpose. . . . It is through this unity that we are to convince the world of the mission of Christ, and bear our divine credentials to the world.”6 Without spirituality, the mission of the church will never succeed, nor will the latter rain of the Holy Spirit be poured on her no matter how ardently prayed for.

When, after Christ’s resurrection, His disciples reached spiritual unity, they received the power of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. The same spiritual unity empowered Adventist mission in its early stages. More than a century later, however, the same mission remains unfinished. We have made great strides in extending the Adventist presence around the world through well-organized institutions. Yet, large sectors of the planet have no Adventist presence, in other areas, mission is stagnant; and even in areas where Adventism seems to be flourishing, the mission remains unfinished. Increasingly, missionary efforts seem to stem from dutiful obligation or selfish motives than from an inner passion for dying souls. Instead of being a natural outgrowth of every believer’s total commitment to Christ, mission is becoming the task of a few “church growth” professionals.

Adventists have long been aware of their desperate need of the Holy Spirit’s latter rain. Yet, in practice they continue to hope that new methodologies will finish the mission or/and that God’s eschatological intervention will generate some financial or natural disaster that may unleash the latter rain. Although for some these arguments are persuasive, they fail to answer the question about why God has not intervened yet.

But what if the next move is not up to God but up to the church? What if, while we are waiting for God, God is waiting for us? Perhaps we are missing the simple point that mission depends on the unity of the church, the unity of the church on spirituality, and spirituality on vision (the mission-church-spirituality-vision connection). If this is the case, the finishing of the mission of the church requires that we should immediately begin planning for a denominational-wide retrieval of the Adventist vision and its application to the spiritual lives of every Adventist to achieve the unity of the church, which is the condition to receive the latter rain of the Holy Spirit. The urgency of times requires that we do this simultaneously at all levels of church life—including institutions and administration.

Vision and the Neutralization of Scripture

Forgetting the vision. Obviously, Adventism did not lose its vision overnight but through a period of time surprisingly short. A brief historical review of Adventism’s formative years (1844–1850), the Minneapolis Conference (1888), and the pantheism crisis (1903) provides adequate historical markers to draw a broad tentative picture of an otherwise very complex historical reality.

In a few formative years, Adventists discovered their vision in Scripture, and by applying it to Scripture as a whole (sola scriptura), they encountered a complete system of truth. However, only a few years later at Minneapolis, Ellen G. White was deeply concerned over a worldly spirit in the church. According to her, the cause of this worldly spirit was the laziness in personal Bible study (spiritual disciplines) of church members and leaders.

After the formative years, Adventists passionate about their discovery of a complete harmonious doctrinal system eagerly shared it with others. New members received the Adventist doctrine through preaching and Bible study. However, they did not go through the process of discovery themselves. They understood and believed in the sanctuary, but they did not truly see how it works as a vision shaping the Adventist system. Instead, the sanctuary was received by new generations of Adventists as a doctrine among many others rather than as the vision opening to view a complete and harmonious system. They were accepting Adventist doctrines as information (head knowledge) rather than as spiritual food (heart knowledge). Without understanding the sanctuary as vision, they began to trust in information received from sources other than Scripture. Tradition was, ever so slightly, entering into the Adventist community.

Yet new converts pressed on to discover new truths (doctrines) in Scripture. The vision-spirituality-church-mission connection suggests that in doing so they implicitly used a vision. Most of them by default and the presence of the formative pioneers, notably Ellen G. White, continued to operate within the boundaries of the Adventist vision. Others, reading other theological sources, began to use other visions. John Harvey Kellogg’s bright mind led him to embrace and apply the pantheist vision to Adventism. The church survived this alluring heresy only through God’s direct supernatural intervention by the prophetic means of Ellen G. White.

This was the greatest crisis ever to confront Adventist leaders, precisely because it sought to replace the sanctuary as Adventist vision and advance a completely different vision, system of truth, spirituality, church, and mission. Though it was checked for the moment, Ellen G. White anticipated a future recurrence in the church of some form of pantheism. The sad fact is that, from her day to ours, Adventists have continued to communicate and receive doctrine, paying no attention to the vision role of the sanctuary doctrine or the pillars of the Adventist faith.

As successive generations of Adventist leaders no longer used the sanctuary and the pillars of Adventism as vision, they implicitly began to use others. In recent times, particularly with Adventist universities and scholarly research thriving in Adventism, the classical and postmodern visions, implicitly or explicitly, have been at work, guiding the thinking, spirituality, worship, and mission of many Adventist leaders. To most Adventists, the doctrine of the sanctuary is no longer relevant.

The neutralization of Scripture. As new alternate visions operate in the minds of Adventist leaders, Scripture is simultaneously used and neutralized. The neutralization does not eliminate the use of Scripture, even as spiritual discipline, but renders it ineffective to the life of the church.

During some recent studies, I began to read Vatican II documents and noticed a surprisingly high use of Scripture accompanied by a surprisingly low use of philosophy. My first thought was, They are becoming Adventists! Careful study of Roman Catholic literature, however, reveals something else. In their centuries-long quest to win Protestants back to their fold, they discovered that using Scripture and certain Protestant phrases proved a most effective tool. The trick is that behind their usage of Scripture and Protestant phrases, they maintain the classical vision to interpret Scripture, thus rendering any biblical commitment ineffectual.

For instance, the classical vision perfectly fits the historical-critical method of interpretation that stands on the evolutionary assumption that religious truth evolves historically (panentheistic vision). In this context, Scripture is used but considered to be an allegory, myth, or symbol. Thus, exegetical research is used to dismantle the Protestant conception of Christianity. Interpreted in the context of the classical vision, texts are used selectively to support tradition. This leads to a more foundational neutralization of Scripture in spirituality and worship. The Bible is summarily read and combined with other sources and practices. Even in American Evangelicalism, the Bible is no longer studied, preached, and believed, but rather ignored and replaced by an ever-increasing number of new spiritual and liturgical practices pasted together with the emerging new sacrament of popular-beat-intensive-dancing-style music.

The new and improved “Evangelical” version of Catholicism and the Emerging Church movement witness to the success of Vatican II policies. These events originated from the subtle and seemingly small change from the biblical sanctuary vision to the classical Neo-Platonic vision that is shared in common by both Roman Catholics and Protestants. A shared vision (classical and/or postmodern) is the ultimate ground on which deep ecumenism stands. Adventism is not immune to these events. In the absence of a solid and global retrieval and application of the Adventist vision through the pipeline of our organization and educational institutions, we run the risk of progressively and explicitly embracing classical and/or panentheistic visions as predicted by Ellen G. White.

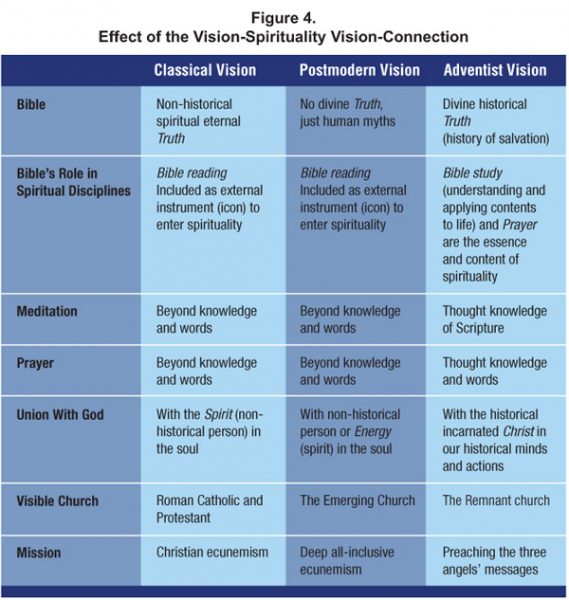

Figure 4 helps us to outline the vision-spirituality-church-mission connection of the classical, postmodern, and Adventist visions by listing the way they affect the practice of spiritual disciplines, the identification of the visible church, and the nature of her mission. The top row lists the visions, and the left column lists relevant spiritual categories.

These trends are already operating within Adventism to promote the neutralization of Scripture. Their strong proponents are in favor of old (classical) new (postmodern) worship styles and spiritual disciplines because these fit with their advocacy of the historical-critical method and evolution. Implementation of these worship styles and spiritual disciplines in Adventist institutions indicate that the classical and/or postmodern visions are already at play. Explicitly embracing and applying a new vision in place of the Adventist sanctuary vision will signal the end of the Adventist Church and her God-given mission. If nothing is done at a global level in our institutions and churches, this event will take place. Fortunately, there is yet time, and much that can be done to avert such a turn of events.

Vision and Method: Maximizing Human Resources

Some may think this all advocates a “head knowledge” agenda for the church. More head knowledge will not change anything. Others, especially those in the General Conference administration, will correctly point out that this proposal is not new, as they have already enacted excellent global initiatives on prayer, personal Bible study, spirituality, and discipleship. These efforts are moving the global church in the right direction. Yet, respectfully, that there is much more that the General Conference and the institutions of the global church can do to bring Adventism back to the Bible. Essentially, they can lead the world church in recapturing and applying the Adventist vision.

The way to overcome the neutralization of Scripture and finish the mission of the church is simple. The biblical vision must be retrieved and applied globally, at all levels of church ministry and institutions. Although simple, this task is also huge. What makes this simple task so massive is its complexity and the possibility that at the present time, the human resources of the church may find themselves unknowingly operating from a diversity of conflicting visions. Complexity means that both the task and the situation have many interlocking parts that together make up both the task and the present situation. The greatness of this task implies that no single person, committee, or institution can accomplish or finish it. Furthermore, its accomplishment requires the combined efforts of all Adventists around the world.

The Complex Situation

(1) Institutions

Although the church is a spiritual community that gathers around Jesus Christ, its existence and operation require material resources and institutions. Three different yet harmoniously coordinated types of institutions facilitate the work of the Adventist Church: church administration, educational and medical institutions, and local churches. In turn, these institutions require the existence of human resources capable of performing the tasks necessary to reach their respective goals. The task of retrieving and applying the vision to the spiritual life and mission of the church properly belongs to the administration, educational and medical institutions, and local churches. However, since educational institutions shape the mindset of church leadership, the task of retrieving and applying the Adventist vision primarily falls within the scope of educational institutions, particularly Adventist universities. For as the educational system goes, so goes the church.

(2) Pastors and teachers

But churches and institutions go as their pastors and teachers go, and all of them have, implicitly or explicitly, a vision that determines how they think and where they go. And their visions come from what they have experienced in their homes, communities, churches and schools (tradition). In the context of the loss of the Adventist vision, doctrinal illiteracy, and neutralization of Scripture, several conflicting visions are presently operating in the mind of educators (pastors and teachers), resulting in confusion among leaders and laity.

This situation affects the ministry of the more than 19,000 pastors and nearly 107,000 primary, secondary, and tertiary Adventist educators around the world.7 Among them, more than 14,000 Seventh-day Adventist tertiary/university teachers play the most significant role because in their everyday ministries, they are closer to the more subtle and technical aspects of the retrieval and application of visions in the community of faith.

(3) Sola scriptura

If several visions are operating within the church, how can it become of one mind and spirit and rally around the Adventist vision? Since the embrace of any particular interpretation of vision is a matter of faith, the Adventist vision must not be forced on anyone, even Seventh-day Adventists leaders. Such would preempt the goal of global spiritual unity and the fulfillment of the final mission of the Christian Church to prepare the way for Jesus’s soon return.

Scripture is the one thing that may hold the Adventist together because it is the only place where there is a direct and detailed revelation of Christ’s history of salvation. Adventists should go back to embrace the sola scriptura principle (Fundamental Belief No. 1). Because sola scriptura affirms that Scripture (Old and New Testaments) interprets itself, embracing this principle automatically means the rejection of Christian tradition and of the classical and postmodern visions.

We know Scripture is a light to our path (Ps. 119:105). However, when the psalmist affirmed “in your light do we see light” (36:9), he recognized that vision of Scripture (light) must also originate in God (light) and therefore implicitly affirms the sola scriptura principle. Recognizing that thinking and acting implicitly or explicitly applies a vision (set of guiding interpretive principles), we should deal with this issue and resolve it in the light of Scripture. However, those holding to extra-biblical visions, like the classical and postmodern, will be drawn to other spiritual communities. Yet, “God will have a people upon the earth to maintain the Bible, and the Bible only, as the standard of all doctrines and the basis of all reforms.”8

Consequently, the process of deconstructing our own personal and institutional visions and placing them under the scrutiny of God’s Word is the first necessary step toward spiritual unity and the latter-rain power for missionary global engagement.

(4) Adventist vision